Untreated sewage pollutes water across the country

The main concern when heavy rains cause combined sewage overflows is for public health. Untreated wastewater can contain bacteria, viruses, microplastics, pharmaceuticals, toxins and heavy metals.

TheStar.com

April 11, 2018

Ainslie Cruickshank

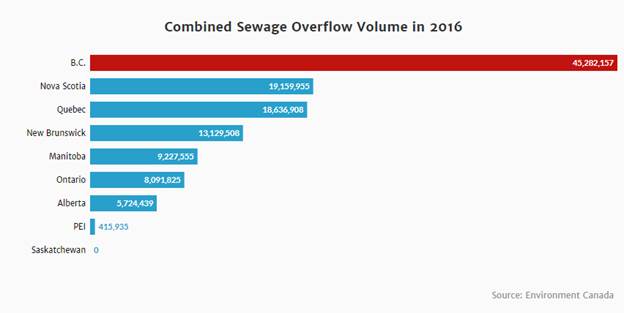

Nearly 120 million cubic metres of untreated sewage and runoff entered Canadian waterways in 2016, StarMetro has learned.

That’s roughly the same amount of water that roars over the edge of Niagara Falls over the course of 12 hours — except it’s not whitewater spewing from these pipes. It’s murky, brown and a little bit chunky.

Environment Canada provided the 2016 figures, the most recent data available, at StarMetro’s request.

In combined sewer systems, the pipes that carry rainwater runoff also carry sewage from homes and businesses to the treatment plant. During heavy rains, these pipes can end up carrying more wastewater than the plant can handle, so they have overflow points where the wastewater can pour directly into a waterway, like a river or lake. It protects the treatment plant from being overloaded, but it can put human and environmental health at risk.

“Anything that you’re flushing is going directly into the stream or receiving waters,” said Sarah Dorner, a Canada research chair in source water protection.

That means pathogens — bacteria, viruses or other harmful micro-organisms — could end up in waterways used for recreation or even drinking water.

While drinking-water treatment systems are typically equipped to handle pathogens, some parasites are more resistant, she said, adding the best way to ensure clean drinking water at the tap is to start with clean drinking water at the source.

British Columbia was responsible for almost 40 per cent of the sewage overflows across the country in 2016.

The risks to human health were highlighted this week by the B.C. Centre for Disease Control. About 40 people have reported acute gastrointestinal illness after eating raw oysters since early March, and norovirus was confirmed in some of those cases. As a result, two oyster farms in B.C. have been closed.

The most probable cause, according to the centre, is human sewage in the ocean. While authorities haven’t pinpointed the source, it could come from various places including combined sewage overflows or discharge from septic systems, explained Marsha Taylor, an epidemiologist with the centre.

“It’s important for people to know that human sewage in our waters may be impacting some of the food we eat,” Taylor said. “It’s an important issue to a lot of us that live so close to the water.”

“It absolutely concerns me,” said Lauren Hornor with Swim Drink Fish, an organization focused on water protection.

Hornor noted it’s not just pathogens from human waste that are a concern. The waters draining from combined sewer overflows can also contain oil and grease from cars, microplastics, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals and other toxins.

“So much of who we are as a community can be reflected in how we treat our waters,” she said. “We are really a country of waterscapes.”

While Hornor said she believes cities are moving in the right direction – for example, the City of Vancouver aims to separate all of its combined sewers by 2050 – she thinks the public should be notified in real time when sewage overflows are happening so they can make informed choices about using water.

It’s “alarming” that some cities don’t currently notify people when sewage overflows are occurring, she said, “because it means recreational water users could unknowingly swim or come into contact with those contaminated waters.”

Data provided by Environment Canada shows B.C. was responsible for the highest volume of sewage overflows across the country in 2016, and that doesn’t include the untreated sewage released on purpose in cities like Victoria, which doesn’t yet have a sewage treatment plant.

But combined sewage overflows remain a persistent concern in other provinces as well.

Nova Scotia, the second-worst offender, released more than 19 million cubic metres of sewage and runoff in 2016.

Ontario released more than eight million cubic metres.

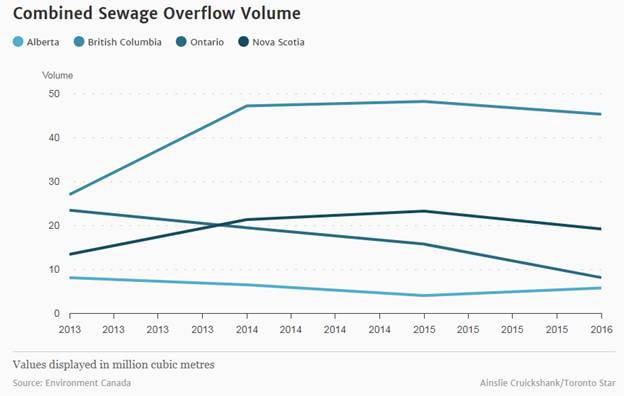

Alberta, which released more untreated sewage in 2016 than in 2015, saw five million cubic metres of untreated sewage and wastewater flowed into waterways.

Overall, the total volume of untreated wastewater released across the country decreased from 2015 to 2016.

Dorner cautioned there could be various reasons for that. It could be that cities across the country are moving to address the issue, either by separating their stormwater and sewage systems or through other initiatives to capture more rainwater. But the amount of rainfall is also a major factor in how much wastewater overflows each year.

Some regions, including Vancouver and Ottawa, are expected to see more rainfall as the climate changes, which could mean more sewage and runoff flowing untreated into the environment if cities don’t continue to take action.