Scooch over: Toronto has room for more density, study says

Toronto’s population could triple and still be less dense than Brooklyn, N.Y., a Fraser Institute report suggests.

TheStar.com

Jan. 9, 2018

Tess Kalinowski

Slow-moving roads, the subway squish and mushrooming skyscrapers might be the most obviously irksome signs of Toronto’s growing population density.

But there’s still plenty of room for more people in The Six before it approaches the top of a list of 30 high-income, international cities, says a study by the Fraser Institute being released Tuesday.

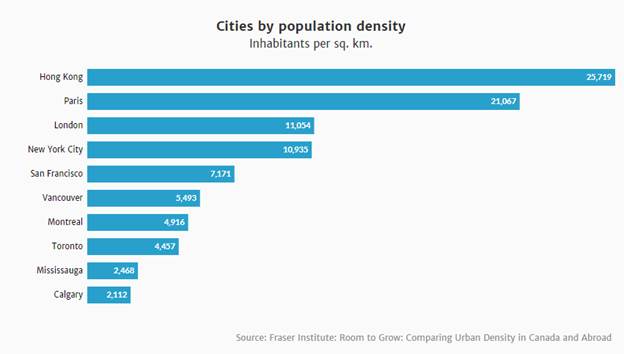

The B.C.-based think tank put Toronto 19th among the cities it ranked, with Hong Kong, Paris and Athens in the top three spots, respectively.

There were 4,457 inhabitants per square kilometre in Toronto, compared to just over 11,000 in London and New York. Tokyo had 25,719 people per square kilometre.

In Canada, Vancouver and Montreal were both considered denser than Toronto based on population per square kilometre with 5,493 inhabitants and 4,916, respectively.

“Canadian cities like Toronto, which are experiencing an affordability crunch, can accommodate much more housing supply. There’s a lot of room to grow, especially upward,” said senior policy analyst Josef Filipowicz, who wrote “Room to Grow: Comparing Urban Density in Canada and Abroad.”

But small apartments in highrise buildings aren’t the only way for cities to grow denser, he said, citing the example of Brooklyn, N.Y., which wasn’t in the list of 30 cities but appears in an appendix to the study. It had 14,541 people per square kilometre.

“Brooklyn is a third the size of Toronto but has the same population and is not necessarily a whole bunch of tiny units,” Filipowicz said.

“Traditionally Brooklyn’s not associated with skyscrapers. It’s known for the brownstone apartments and townhomes. Density doesn’t have to take any particular shape or form. It can offer a whole number of different shapes. That’s ultimately up to the people producing that density, either builders or the city staff,” he said.

The Ontario government’s anti-sprawl Places to Grow Act has made density a thorny subject in the Toronto region, where some economists and builders have suggested that containing development to designated areas is driving up the cost of housing.

Filipowicz acknowledged that it is difficult to measure density. His study did not use metropolitan centres such as the Greater Toronto Area, which, he said, could have produced far different results.

Instead, the Fraser Institute findings were based on core cities and, as much as possible, eliminated non-developable areas inside those boundaries. In Toronto, for example, a 17-square-kilometre area of farmland in the city’s northeast with a population of about 800 was not included in the study’s density calculation.

All the cities included were identified as high-income by the World Bank last year and each had a population of at least 600,000.

The study concludes that density doesn’t necessarily correlate to a lower standard of living.

It overlaid density on an annual livability study called “Mercer’s Quality of Living Ranking.” It put Barcelona and Athens 45 rankings apart, even though both have similar population densities.

Housing affordability also doesn’t necessarily correlate to density either, as each city has different demand and supply issues, Filipowicz said.

“We do see places like Tokyo have pretty modest price growth, just like Houston. Both those cities seem to build a lot but are completely different in the way they’re actually physically formed,” Filipowicz said.

The Fraser Institute study is important to Canadians in cities such as Toronto and Vancouver, where rental vacancy rates are contributing to the challenge of affordable housing, he said.

“It’s important to underscore just how much room there is to boost the housing supply,” Filipowicz said, adding that, “more housing supply is one of the best ways to stem rising housing costs.”