Census data says you’ll make a lot more than your immigrant parents, but your kids won’t make as much as you

A study of cense data examines the ethnic differences in after-tax incomes across first, second and third generations of immigrants by ethnicity.

TheStar.com

Jan. 21, 2018

Nicholas Keung

Children of immigrants make a lot more money than their parents but their kids won’t make as much as them, the latest census shows.

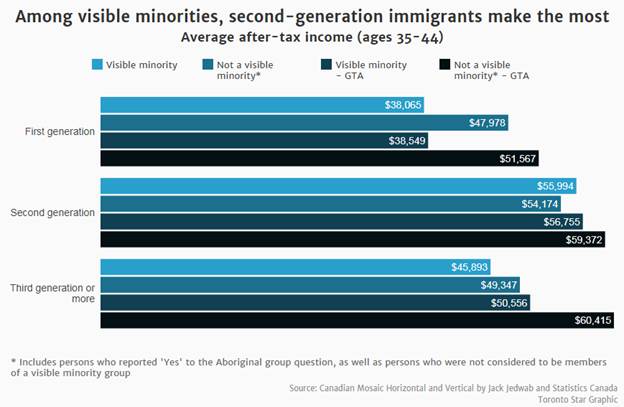

While visible-minority immigrants tend to earn less than their white immigrant counterparts, their kids more than make up the income gap between the two groups and also outperform their white peers in the second generation, according to a report by the Association of Canadian Studies based on 2016 census data.

Part of the study, to be presented at a national conference in March on immigration and settlement policies, examines the ethnic differences in after-tax incomes across first, second and third generations of immigrants by ethnicity in the prime working age between 35 and 44.

For immigrants — white or non-white — that upward socioeconomic mobility based on earnings fizzled by the third generation when all groups, except for the Korean and Japanese, made significantly less money than their second-generation parents.

According to Jack Jedwab, the report’s author, visible-minority immigrants made an average of $38,065 a year, compared to $47,978 earned by white immigrants.

Overall, children of visible-minority immigrants made a 47 per cent leap in their average earnings above their parents, making $55,994 annually, surpassing their white second-generation peers, who made $54,174 annually or 13 per cent more than their own parents. (The white group also includes those who self-identified as Aboriginal, who makes up 6.1 per cent of the group.)

While all children of immigrants of colour did better than their parents, some communities fared better than others.

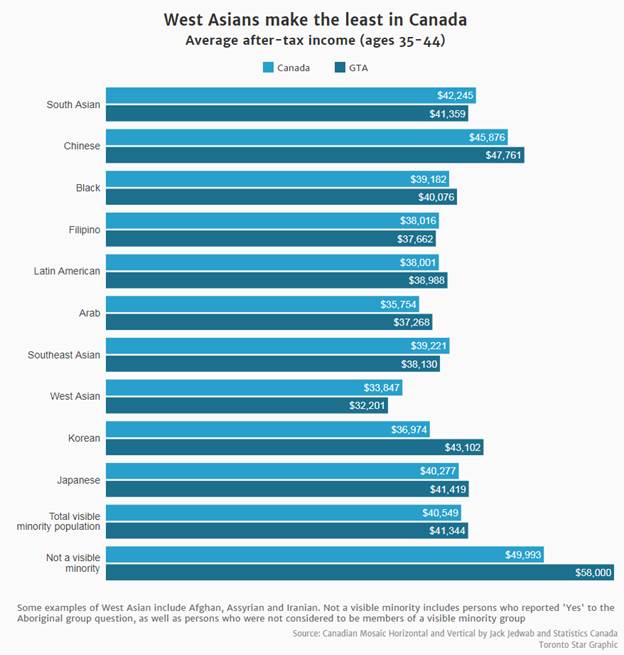

Second-generation South Asians made the most progress, earning an average of $62,671, up from $38,978 from their immigrant parents. Their Chinese peers, who had the highest average annual income of all groups at $65,398, made 50 per cent more than first-generation Chinese immigrants who made $43,085.

“The entire second generation enjoyed a higher mobility though some communities were faring better than others,” noted Jedwab, who teaches sociology and public affairs at Concordia University.

The higher socioeconomic attainment, he said, can be partially attributed to immigrant parents’ expectations on their children to make up for the sacrifice they made for the move and seize on the better opportunities Canada has to offer.

“Education is certainly a key explanation and I would suggest that the value that children of immigrants attach to higher education is greater than is the case for the grandchildren of immigrants,” said Jedwab.

“Children of immigrants don’t push their own kids as hard. I don’t know that I would describe them as helicopter parents. Also the support network or social capital is likely stronger amongst the children of immigrants than amongst the third generation where probably the degree of mutual support is weaker.”

Growing up in Canada, Toronto-born lawyer Haniya Sheikh said she saw how hard her Pakistani immigrant parents worked to make a new life and give her the best opportunities in their adopted homeland.

“They were my role models. The big deal for them was work ethic. You always work hard and put your best foot forward,” said the 43-year-old woman, whose parents, both high school graduates with some university studies, came to Canada in 1967 from Tanzania after living across Europe.

(Her father was a retired appraiser for an insurance company and her mother was a deputy registrar with the Health Services Appeal and Review Board before their retirement.)

“They never complain and are grateful to be in this country. My parents had subtle expectations that you would do well, but no one would beat you with a stick. Some of the expectations are self-imposed.”

Her father, for example, once commented “you are almost there” when she came home with a 97 per cent on a biology test. When she set her sights on becoming a lawyer, he asked her again and again if she was sure she didn’t want to be a doctor.

Now a mother of four, Sheikh said she was shocked to learn her children would likely have lower educational attainment and earnings than her, according to the census data.

She said she and her immigrant husband, Samir Khan, also a lawyer, have instilled the same kind of ethics and values into their kids — a boy, 3, and three girls, 12-year-old twins and a 10-year-old.

However, “our definition of success has changed from 30 years ago,” said Sheikh, as earlier generations of immigrants would define success as obtaining multiple university degrees and making a lot of money. “Education is still very important,” she said, “but there are many paths to success.”

Hashmat Arshad, whose family came to Canada from Kenya by way of England, said his mother was very strict with him and his two elder sisters, both university graduates, when growing up.

“The pressure was definitely there. We had no time to slack. Every summer, my mom would give me homework. I had to study the dictionary or she wouldn’t allow me to go out and play,” said the 23-year-old, who has a degree from York University in psychology and a diploma from Seneca College in vocational rehabilitation counselling.

“My mother was a single mother. Starting over again in Canada was hard. She wanted us to take advantage of Canada’s education system, which is the best in the world. She got disappointed if I didn’t get the highest grades.”

Arshad feels first-generation immigrants are strict in raising their kids because they try hard to maintain their cultural and heritage in the same way their parents raised them back home.

“As a second-generation immigrant, we are merging our culture and heritage with our Canadian values, which are more liberal. We are more open to new ideas and other cultures,” he said.

Like Sheikh, Arshad, too, was surprised that third-generation immigrants are more likely to have lower education and incomes than their second-generation parents.

“Maybe technology is a factor. It makes everybody lazy because everything is so accessible and you don’t work as hard,” said Arshad.

Compared to other ethnic groups, second-generation Latin Americans and Blacks made modest improvements, making 20 per cent and 22 per cent respectively more than their immigrant parents.

Both groups lag behind the $54,174 average income among their second-generation white peers.

That generational gain, however, reached a plateau for almost all ethnic groups, said Jedwab.

Average earnings by all visible minorities in the third generation fell by 18 per cent to $45,893 from $55,994 for the earlier generation as their white peers saw theirs dropped to a lesser extent by nine per cent to $49,347 from $54,174.

Both third-generation Koreans and Japanese actually saw a modest increase in earnings by eight per cent and seven per cent respectively.

Jedwab said the overall increase in second-generation earnings and their upward mobility across the board indicate Canada is still “a land of opportunities” for immigrants.

Despite the second-generation’s success, Jedwab said Canada must do a better job at matching the skills of the first-generation immigrants as many of them are arriving with not just a university education but multiple degrees.

However, he believes the income decline among the third generation is largely the result of the “devaluation” of the university education while the gaps seen among different ethnic groups may indicate how some groups are better than others at adapting to the changing labour market in a knowledge-based economy.

How the third generation fares in earnings?

“Back in the days, immigrants were saying we’re sacrificing for our children so they could do better, but immigrants now with university degrees are saying I’m here to improve my own conditions,” he said. “They come with the mindset this is not only about the future of my kids.”