Fifty years later, just about everyone loves Toronto’s weird, unlikely City Hall

nationalpost.com

Sept. 1, 2015

By Chris Selley

Send a Torontonian back in time to 1957 and he might get quite bored quickly. You couldn’t drink until you were 21 and had secured a permit. The international food scene was...embryonic, let’s say. The word “multicultural” had just appeared for the first time in The Globe & Mail. Men were men and bread was white.

Toronto’s legendary inferiority complex was gathering steam, however. Contemporary news betrays a distinct fascination with architectural triumphs in New York (UN headquarters), Sydney (the planned opera house) and elsewhere. And in September, mayor Nathan Phillips announced what remains one of Toronto’s boldest and most successful gambles: an international competition to design the new City Hall, which turns 50 years old this month.

An exhibit at Ryerson University’s Paul H. Cocker Gallery, which opened Monday, looks back at that competition, which saw more than 500 entries, many of them fascinating, submitted from around the world. And it is intriguing to imagine what might have been.

Any of the eight finalists would have been perfectly serviceable. Two were centred on less-than-thrilling slab office buildings. Five were hulking square buildings with an interior courtyard, in some cases containing the council chamber - including one by I.M. Pei and another by John Andrews, in which a subterranean council chamber was visible beneath visitors’ feet through a glass ceiling.

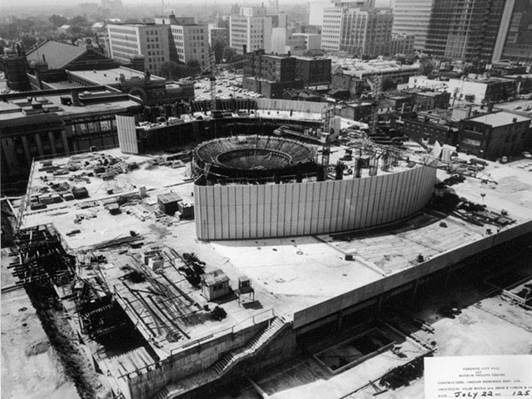

All were centred at the north end of the property; all included plenty of public space at the south end. But none had a fraction of Viljo Revell’s striking, inexplicably welcoming oddness - a clamshell council chamber coddled by twin office buildings, one taller than the other.

“The fact that it’s a curvilinear form in a city that’s dominated by block buildings, that’s dominated by a grid, makes it distinct,” says George Thomas Kapelos, a Ryerson architecture professor who curated the exhibit with historian Christopher Armstrong.

“It opens itself to the public. You can walk right into the interior of the building; you’re not going up a monumental flight of steps...You come into a space where you feel that it’s part of our city, and you are part of the city.”

Indeed, as unique as the building is, as uncommonly bold and incongruous it remains, it’s nearly impossible to imagine the city without it.

Outside, for all Nathan Phillips’ Square’s austere concrete, it certainly seems to have satisfied the competition’s demand for a natural gathering place - whether it’s New Year’s Eve, the Pan Am Games or Jack Layton’s memorial in chalk. Inside, the lobby presents as somewhere Torontonians can engage in their democracy relatively simply and directly, where their elected officials have relatively few places to hide. And even amid the chaos of recent years, the council chamber itself has a dignity about it that somehow implies serenity might be near at hand.

If you ask me, it’s altogether a triumph and worth celebrating. And it’s worth considering how easily it might not have happened.

There were protectionist voices in government and in the architectural community who deplored the idea of inviting non-Canadians to design Toronto’s City Hall. There were complaints about cost: Phillips supported the international competition over a much cheaper and less ambitious plan for the site that had been widely denounced by urban elites (including, notably, young architects).

“(People) are fed up with rising taxes and no one has proved that building a new city hall will lower them,” one Maurice Pushton complained to the Globe. And when the initial $18-million cost approved by voters inevitably began to climb, and climb, the complaints quite rightly intensified.

In many ways, then, Toronto is the same city. What sort of city hall would we build today? We haven’t yet come to grips with the idea of foreign-built subway cars, and we are quite in thrall of celebrity architects. (Just look what we let Daniel Libeskind do to the Royal Ontario Museum.) Would we trust a relatively unknown Finn to design something bold and dramatic and interesting, or would we limit our options, or would we cheap out and wind up with something like Metro Hall?

There’s nothing wrong with Metro Hall, exactly, and it’s impossible to quantify what Revell’s odd concrete thing provides this city. There is much to credit in Toronto’s conservative, risk-averse nature, in its instinctive suspicion of extravagance, whimsy and monumentalism. And the process launched in 1957 wouldn’t work today for some very good reasons.

But most everyone seems to love City Hall, and the square out front of it. On its 50th birthday, it’s worth considering that one of our greatest landmarks stems from a fairly thumping rejection of some fundamental character traits.