‘Fire-Medic’ proposal pits firefighters against paramedics

Paramedics fire back at a new proposal by the Ontario Professional Fire Fighters Association for firefighters to perform more medical interventions.

TheStar.com

July 7, 2015

Rachel Mendleson

The perennial turf war between firefighters and paramedics is heating up again, with a new proposal from the Ontario Professional Fire Fighters Association (OPFFA) for firefighters to perform more medical interventions.

Firefighters and paramedics each make a case for or against the creation of so-called “Fire-Medics.”

The problem

According to the OPFFA’s proposal, growing demand for pre-hospital care combined with budgetary pressures has placed a chronic drag on paramedic response times.

Although firefighters are currently dispatched alongside ambulances to certain medical calls, and often arrive on scene first, the interventions they can provide are generally limited to administering oxygen or a defibrillator and, in some cases, using an EpiPen.

“Everything we’re proposing is predicated on response times,” says OPFFA president Carmen Santoro.

Paramedics agree there can be hurdles to arriving on scene as quickly as firefighters. But they say the OPFFA’s proposal ignores one of the biggest problems: long wait times for hospital beds, which ties up ambulances delivering patients to emergency rooms.

Jeff van Pelt, president of the CUPE Ambulance Committee of Ontario, says the firefighters’ proposal “is about protecting their own jobs” amid a drop in fire-related calls.

“There isn’t a lot of work for them left anymore. They made themselves obsolete by doing an incredible job at fire prevention,” van Pelt says.

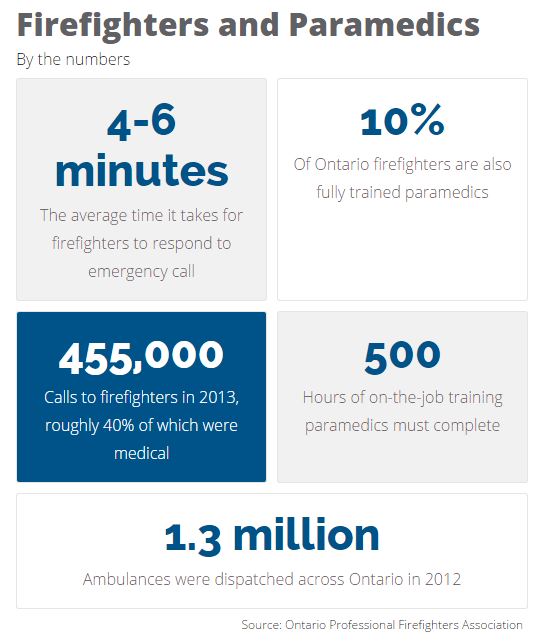

By the numbers

Santoro says it takes an average of four to six minutes for firefighters to respond to an emergency call.

Most of the province’s 11,000 full-time firefighters currently receive basic medical training, including instructions on how to administer first-aid and use a defibrillator. About 10 per cent of firefighters are also fully trained paramedics.

Medical calls accounted for roughly 40 per cent of the 455,000 calls to firefighters in 2013, the OPFFA report states.

Response times are measured differently by firefighters and paramedics, making comparison tough, says van Pelt.

In urban settings, paramedics must arrive within 12 minutes, 90 per cent of the time, but some services do much better. In Durham Region, for instance, the average ambulance response time was just over six minutes in 2013.

Paramedics must complete two years of school, 500 hours of on-the-job training and recertify their skills annually, van Pelt says.

Ambulance were dispatched roughly 1.3 million times across Ontario in 2012.

The solution

The OPFFA says the union’s proposal, which the province is currently reviewing, aims to give firefighters 20 hours of medical training so they can provide “symptom relief,” by administering drugs such as Ventolin and nitroglycerin to treat asthma and chest pain.

The plan calls for eight pilot sites across the province. Toronto, Brampton and Mississauga are among the cities that should be considered, the report states. Program costs are pegged at just over $30,000 a community in the first year.

“This is not about us versus them. This is about the patient and working together to enhance emergency medical response,” Santoro says.

According to van Pelt, 20 hours of training is not enough to equip firefighters with the skills they need to make life-saving decisions.

The best way to free up ambulances and improve emergency access to highly trained medical professionals, he says, is to increase funding to hospitals so paramedics can get in and out more quickly.

“If this was about patient care,” van Pelt says, firefighters “would be advocating to the politicians to increase EMS money, increase hospital money.”