$25-million project reimagines area under Gardiner with paths, cultural spaces

Theglobeandmail.com

Nov. 16, 2015

By Alex Bozikovic

For decades, the Gardiner Expressway has been a barrier between downtown Toronto and Lake Ontario. That promises to change in 2017, as a 10-acre space under the highway becomes a network of pathways and gathering places that binds a fast-growing part of the city together.

This is the promise of a bold new public-space project, which will be formally announced on Tuesday morning. Supported by a $25-million private donation, the initiative will remake an area under the Gardiner - stretching over 1.75 kilometres – into a place unlike any other in the city.

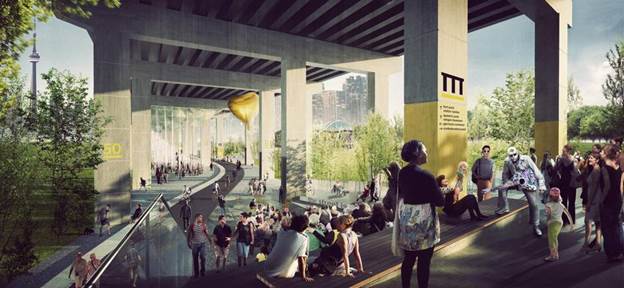

Called Project: Under Gardiner, it would combine a walking and cycling trail with covered public spaces that can be used for markets, meetings and performances. “It’s not just a park, and it’s not just a trail,” Adam Nicklin, a partner at the landscape architecture firm Public WORK and one of the lead designers, told me last week. “It is a series of spaces that can be a showcase for all that is exciting about Toronto.”

The first phase of the project is scheduled to start the planning process shortly and to be completed, quickly, by July, 2017. It will include a continuous trail from near Strachan Avenue all the way to Spadina Avenue, punctuated by two major elements: an outdoor “grand stair” at the intersection of Strachan and a pedestrian bridge that spans Fort York Boulevard.

The design vision put forward by Public WORK and urban designer Ken Greenberg uses the structure of the highway as a canopy for a string of loosely designed outdoor “rooms.” Some of these would serve as performance spaces – and indeed the project will have a staff curator to organize cultural events. The designers imagine that later phases could include buildings, such as an “innovation hub” of art, design and fabrication studios.

The construction and the operation of Under Gardiner reflects an unusual partnership. Built by the public agency Waterfront Toronto and owned by the city, the project will be funded with $25-million from local philanthropists Judy and Wil Matthews. They, and the city, are studying whether the space could be run by a park conservancy, a not-for-profit institution that would work in tandem with the city.

Toronto’s parks and public spaces have never seen a donation this large, or that sort of partnership. In an interview on the weekend, Mayor John Tory said Under Gardiner might set an example for other collaborations between the city and private donors, including some kind of park conservancy model. “I think it is going to have a huge positive impact on the city,” Mr. Tory said of the project. “I’m very hopeful that this stunning example set by the Matthews will be replicated many times over.”

This is philanthropy directed to an unusual target: the space under an elevated highway. And yet this strip of land, largely unused, spans a set of neighbourhoods - from Liberty Village through CityPlace and the central waterfront – which now house more than 70,000 residents and continue to grow. Most of those people live in new condominium towers placed between rail lines, the expressway and busy arterial roads.

“This area is the new frontier on which the city is growing,” Mr. Greenberg said, “just as old infrastructure becomes available for reuse and reinvention.”

What has been missing “is a patch to hold these areas together,” he said.

Mr. Greenberg helped to conceive the project with Judy Matthews, a retired city planner who worked with the city of Toronto and the University of Toronto. Ms. Matthews said in an interview that she believes that in this area of the western downtown, “there is an explosion of growth and an enormous gap between that growth and the provision of public amenity.”

When Mr. Greenberg showed her the space under the Gardiner, she had never been there. “But I quickly went ‘aha’: It is incredible, the scale and the monumental quality of that space.”

This part of the Gardiner is raised about 15 metres - or nearly five storeys - in the air. It rests on 55 “bents,” U-shaped assemblies of concrete columns and spans. The civic potential of this space has already been suggested by the spectacular Fort York Visitors Centre, which sits in the path of the project.

For Public WORK, the highway’s bone structure provides a powerful aesthetic starting point. “We realized very quickly that we should work with what is there,” said Marc Ryan, who leads the office together with Mr. Nicklin. “It is so powerful as it is, and we don’t want to destroy that. The design is less about aesthetics and more about curation and choreography.”

This move, to make a beautiful place out of unused infrastructure, reflects the role of landscape architects in today’s cities. “We realize we’re not going to find new public realm in the conventional places,” Mr. Ryan said. “There are no more Central Parks to be built.”

Instead, the big projects involve reclaiming leftover industrial land or infrastructure - “while the glacier of industry recedes from the downtown,” as Mr. Greenberg said.

The High Line, a linear park made from a disused rail line in Manhattan, brought public attention to this way of thinking when it opened in 2009. It became instantly, wildly popular, and has spawned imitations in other cities, including Chicago.

But the High Line is elaborately designed and expensive - its first half-mile cost $152-million (U.S.), funded in part by private donations. Toronto’s Under Gardiner will be much cheaper, and Mr. Ryan said the landscape architects are looking at “a design language that is raw, and has soul.” He raised the idea of salvaging discarded bricks and rubble from the Leslie Street Spit to serve as paving materials.

Project: Under Gardiner would also serve as an important link for cyclists and pedestrians in and out of the downtown core. It links up with an extension of the West Toronto Railpath, scheduled for 2018, and also with an emerging network of green spaces centred on Fort York. A new pedestrian bridge at Fort York, which will begin construction next year, will cross the downtown rail corridor and link the fort with existing or planned parks in Liberty Village and in the King-Bathurst area.

It also connects with a string of landscape projects that are transforming the central and eastern waterfront. Before they founded Public WORK, Mr. Nicklin and Mr. Ryan worked respectively for Toronto’s DTAH and the Rotterdam-based firm West 8; in those jobs, they collaborated on a plan for the Central Waterfront, including the popular WaveDecks around Harbourfront. The Central Waterfront Plan led, this summer, to the renovation of Queen’s Quay West.

Project: Under Gardiner puts a different spin on a subject that came up during this year’s debates around the Gardiner East: the presence of an expressway in the downtown. While the city is now studying how to rebuild the Gardiner East - a decision that, as I wrote in May, represents poor planning and a huge unnecessary expense – the western section of the Gardiner is a different story.

Mr. Greenberg is a strong advocate for the demolition of the Gardiner East, but the western section “isn’t going anywhere,” he said. It is heavily used, and any effort to bring it down to ground level, Mr. Greenberg pointed out, would be hugely complex and expensive. This view is uncontroversial; former chief planner Paul Bedford, another foe of the Gardiner East, is among dozens of civic leaders who have signalled their support for the Under Gardiner plan.

The city now has more than $145-million worth of construction work under way or planned to repair sections of the western Gardiner. The Under Gardiner team suggest that this work could be combined with the construction of the park corridor.

Mr. Greenberg said city staff, in private discussions, have shown “unprecedented goodwill and resourcefulness” toward this project. And Ms. Matthews, for her part, hopes that her and her husband’s ambitious effort will create a quick result and also set an example. “If you want to make your city one level better,” she said, “sometimes you have to step in and help.”