How the Ford government’s love of MZOs is increasingly benefiting private developers with ties to PC and local politicians

Noor Javed. Steve Buist

Thestar.com

June 14, 2021

The mayor’s unusual request blindsided his colleagues.

In October, Vaughan Mayor Maurizio Bevilacqua sprung resolutions on his council to approve three special zoning orders that would allow the province to expedite construction projects some of his fellow council members say they knew nothing about.

The developments would be fast-tracked through minister’s zoning orders, or MZOs, a controversial and blunt tool used sparingly for decades that is now being wielded with alarming frequency by the Ford government.

Two of the MZO requests put forward by Bevilacqua were for projects that could add close to 10,000 housing units, and the third for a warehouse on provincially protected land, normally off-limits to developments.

All three, as council members found out later, were associated with the Cortelluccis, a prominent family of land developers based in Vaughan.

“We have never done it this way,” said local councillor Marilyn Iafrate, who unsuccessfully pushed back on the requests, asking for public hearings before making a decision. “No applications, no staff reports, no public hearings. Zero. It was basically like ‘This is what we want. Approve it.’ ”

Once approved, the MZO request goes to the Ontario government. And with Doug Ford at the helm, it’s high season for fast orders. One of the MZOs approved by Vaughan council last Oct. 21 was granted by the province 16 days later -- a decision that can’t be appealed.

The Ford government has handed out 44 permanent MZOs since 2019. Last year alone, it issued 33 -- more than twice as many as the previous government did in 15 years.

Ontario’s prolific use of the zoning tool has upturned a decades-old planning system that had specific processes, protections and transparency built into it, say critics of MZOs, including residents, local councillors and MPPs. And in turn, it has created a system that appears to be less about procedure but more about who you know.

The Ford government says these zoning orders are being used to benefit the people of Ontario. However, a Torstar investigation shows they are increasingly benefiting a select group of prominent land developers with strong ties to municipal leaders and the Ontario PC party.

Iafrate wasn’t the only councillor who wondered what was going on when Mayor Bevilacqua proposed three MZOs.

“Why one (developer) over the other?” said councillor Sandra Yeung Racco. “Is it because they have donated, do we have to treat them differently?”

Vaughan Councillor Marilyn Iafrate unsuccessfully pushed back on the mayor's October 2020 requests for council to approve three special zoning orders to fast-track developments. Iafrate asked for public hearings before making a decision

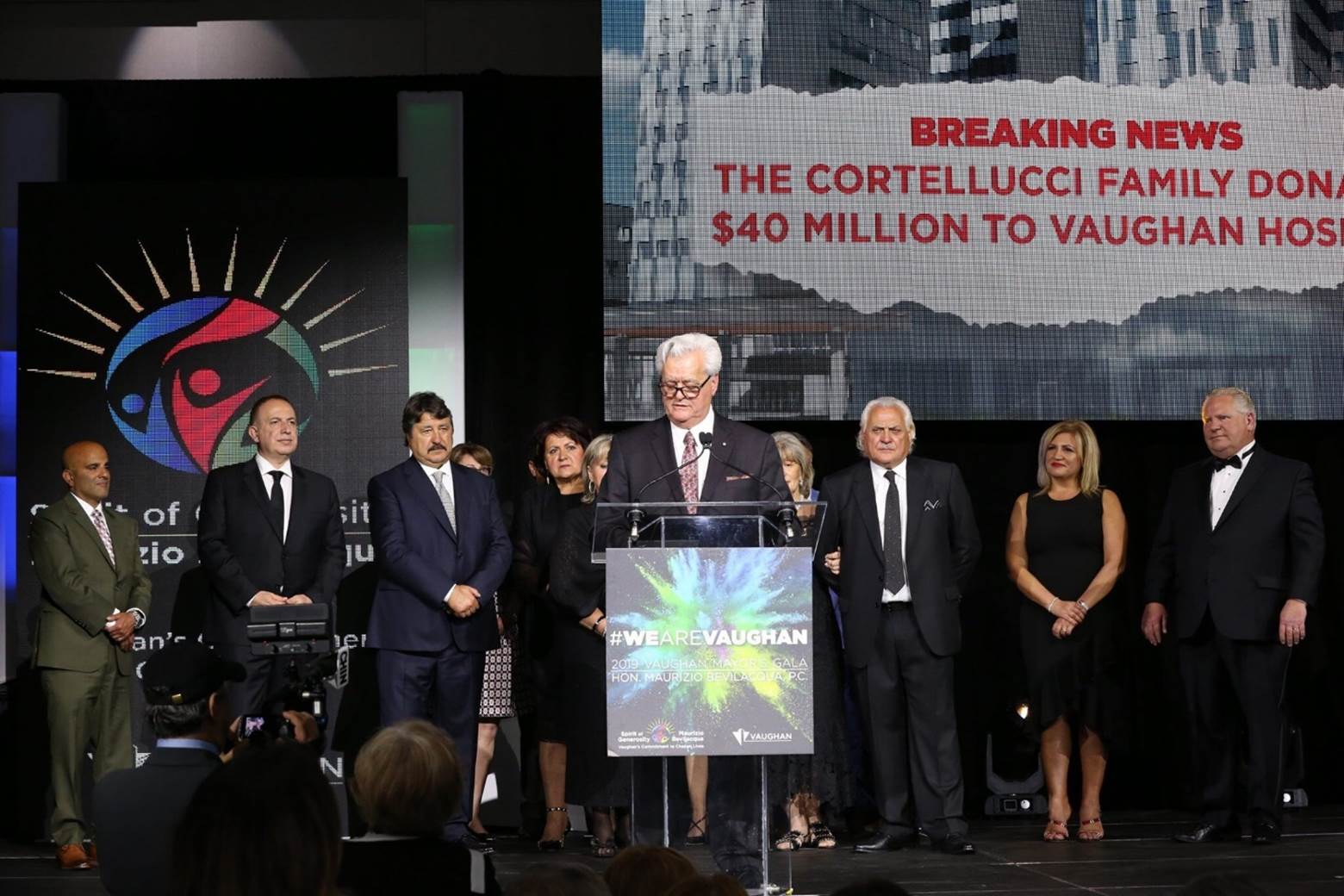

A little more than a year before Bevilacqua introduced the three MZO requests, the Cortellucci family made a $40-million donation to the new hospital in Vaughan that now carries their name. They also donated millions to the city’s first hospice and university campus, on top of tens of thousands of dollars to candidates running for local council and even more to the Ontario Progressive Conservatives.

“An historical evening for the City of Vaughan,” Bevilacqua beamed when he announced the Cortelluccis’ hospital donation at a sold-out mayor’s gala featuring luxury cars on display and an opera singer. He shared a story about how his father, a newcomer to Canada 50 years ago, rented trucks to the Cortellucci family, who were also then starting out.

In attendance were local PC MPP Stephen Lecce and a tuxedoed Premier Doug Ford, who spoke highly of the family’s humility and generosity.

The mayor’s requests for MZOs alarmed a number of residents, too.

In February, they filed a complaint with the city’s integrity commissioner asking why Vaughan “should endorse MZOs at the expense of public consultation,” and “circumvent the local planning process and prioritize this developer’s application, ahead of all other active applications that followed and abided by the local planning process.”

The commissioner reviewed the “informal complaint” and said the mayor was in compliance with city rules. However, she said the process, if left unchecked, could cause council to become a “very permissive body,” allowing its members to act in their own self-interest “rather than in the interests of the municipality or the public.”

The mayor’s request would let the Cortelluccis queue-jump almost 500 other applications before the city that were following the normal planning processes, the complaint said.

Vaughan council passed the mayor’s request for the three MZOs, and the Ford government granted two of them. The third, which would see the removal of provincially significant wetland and forests if approved, is still pending.

It’s not known if the donations played any role in Vaughan council’s decision to ask for the MZOs or the province’s choice to approve them. There’s nothing illegal or improper about developers donating money to politicians and charitable causes.

Mayor Bevilacqua, who noted one of the developments aims to bring in needed public housing, said he acted in the public interest. He said he brought in the proposed MZOs at the request of his staff. “I am just one vote. If the council doesn’t endorse it, it doesn’t go anywhere,” he said. “Ultimately, the province will decide if they want to issue an MZO. I don’t make that decision.” He also said that not every hospital donor got an MZO.

The Cortellucci family donated $40 million to the new hospital in Vaughan that now carries their name, a donation announced at Vaughan's 2019 mayor's gala. Mayor Maurizio Bevilacqua and Premier Doug Ford shared a stage with the Cortelluccis and spoke of their generosity. | City of Vaughan photo

MZOs take precedence over any local or regional council planning decisions. Only the province can hand them out or revoke them.

“We will never stop issuing MZOs for the people of Ontario, the people that need housing,” Ford said earlier this year.

Despite Ontario’s vast size, the Ford government has only issued MZOs in a core of the province that revolves around the GTA.

They have been used to approve a glass factory, giant warehouses, nursing homes and large subdivisions. They have authorized projects on provincial land, helped municipal governments add affordable housing and allowed non-profit groups to build seniors homes.

Of 44 MZOs issued in the past two years, 38 have gone to Toronto, the regions of York, Peel and Durham, and Simcoe County -- some of the wealthiest parts of the province, where population growth is expected to jump in coming decades and land is most expensive.

MZOs are as old as the province’s planning act, established in 1946. Requests for zoning orders are made to municipal councils. If a council votes in favour of the request, it’s submitted to Ontario’s municipal affairs and housing minister, Steve Clark, for a decision.

“MZOs are a tool our government uses, in partnership with municipalities, to get critical local projects that people rely on, located outside of the Greenbelt, moving faster,” said Krystle Caputo, Clark’s director of communications.

The government has emphasized that “every single” MZO issued on non-provincial land was done at the request of the local municipality.

More than half of the first 26 MZOs handed out by the Ford government went to municipalities, non-profit organizations or were used for projects on the province’s own land.

But in the last seven months, zoning orders have been used almost exclusively to help private-sector companies and developers jump the queue and bypass the local planning process.

Sixteen of the 18 MZOs handed out since October have gone to developers, most of whom have connections to the Ontario PCs either through former party officials now acting as lobbyists, political donations or both.

Almost half of the Ford government’s MZOs for private-sector developments have gone to projects associated with just four land developers -- the Cortellucci family, the De Gasperis family, Fieldgate Homes, and Flato Developments, founded by Shakir Rehmatullah.

All four have made large donations to charitable causes, mostly in York Region. Fieldgate and its principals, Jack Eisenberger and the Kohn family, along with the De Gasperis and Cortellucci families have donated a combined total of $600,000 to the Ontario PCs in recent years.

The four groups also donated $358,000 to the Liberals and NDP since 2014 -- all of it before the PCs were elected except for $3,225.

Fieldgate, De Gasperis and Cortellucci were among those highlighted in a recent Torstar/National Observer investigation into the money, power and influence behind the proposed Highway 413.

The story, published in April, revealed that eight of Ontario’s major developers own 3,300 acres of prime real estate near the controversial highway’s proposed route, land conservatively valued at nearly half a billion dollars.

The Kohn family, founders of the Fieldgate Group of Companies, and the De Gasperis family teamed up in 2018 to donate $20 million to the Vaughan hospital.

Developer Silvio De Gasperis, seen here in 2005, said in a statement that there's no connection between the three minister's zoning orders his companies received and his family's political donations and gifts to facilities and hospitals. | Lucas Oleniuk photo

Flato has received five MZOs, the Cortellucci family’s companies have been awarded four and Fieldgate has received three MZOs as part of a consortium. The De Gasperis family has received five MZOs -- three to companies associated with Silvio De Gasperis and two to companies associated with another branch of the De Gasperis family.

The Cortelluccis along with Eisenberger and Kohn of Fieldgate did not respond to requests for comment.

Silvio De Gasperis, owner of TACC Construction, said the MZOs helped push forward much-needed projects that had stalled.

In a statement, he said the pandemic has made it especially difficult to move development projects forward fast enough. “The GTA is behind in meeting the housing needs of the existing population,” De Gasperis said, “causing housing supply shortages and increases in the cost of housing.”

De Gasperis said there’s no connection between the three MZOs his companies received and his family’s political donations and gifts to facilities and hospitals, which are “essential to strong and sustainable communities and are not fully provided for by the public purse.”

“We are a key partner with municipalities and the provincial government in building communities,” De Gasperis said. “We build communities, governments do not.”

In 2018, Flato’s Rehmatullah donated at least $1 million to fund a new cancer clinic at the Markham Stouffville Hospital.

At the clinic’s ribbon-cutting ceremony, Ford was standing next to the developer, each with their hands on the oversized scissors. On the other side of Rehmatullah was Markham Mayor Frank Scarpitti, co-chair of the hospital’s capital fundraising campaign.

On March 5, 2021, Rehmatullah’s Flato Developments received MZOs for two Markham properties.

Flato Developments President Shakir Rehmatullah (third from the left), sharing scissors with Markham Mayor Frank Scarpitti (second from left) and Premier Doug Ford (centre), at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for a new cancer clinic at the Markham Stouffville Hospital. | PaulCalandra.com photo

Markham staff, dozens of residents, and five of 13 councillors had recommended against both. Staff called the MZO proposals “premature” because York region is in the midst of a comprehensive review of land use needs.

Like Bevilacqua, Mayor Scarpitti said there is no connection between donations and MZOs and that the orders were in the public interest, as they would bring in water and sewage infrastructure into northern Markham years ahead of schedule.

“We approved this MZO not because it’s Flato, and not because they are philanthropic. It’s because of the context of where this MZO was located,” Scarpitti said, “and we saw that it would bring mutual benefit to the city, as well.”

That same day, Flato received another MZO for a housing project in New Tecumseth. In 2017, Rehmatullah had donated $50,000 to New Tecumseth’s hospital.

And in 2019, Flato and a partner donated $500,000 to the Whitchurch-Stouffville mayor’s gala. The following year, Flato was granted two MZOs for properties in Whitchurch-Stouffville.

Flato did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Iain Lovatt, mayor of Whitchurch-Stouffville, said the charity was “arms-length” and not directly related to him. “Any donation...has zero influence on my decision making.”

He also said he supported the MZOs as they will bring seniors housing into the community, and develop “walkable, complete communities, which is very much in the public interest.”

In three instances, there's evidence the developer Shakir Rehmatullah, seen here with Premier Doug Ford in 2018, went over the head of the local council and straight to the province with an MZO request. | Susie Kockerscheidt/Metroland

NDP Leader Andrea Horwath described the Ford government’s use of MZOs as “a disgrace.”

“It’s pork barrelling at its worst,” she said. “This government has decided to use it as a way to provide gifts to their developer buddies.

“It’s despicable that they’ve come upon this as an opportunity to increase their access to donations,” she added.

A spokesperson for Ford said the developers identified have donated to the provincial Liberals and NDP as well as the PC party.

“Any attempt to link the MZOs with political connections to the PC party is completely baseless, misleading and not supported by fact,” said Ivana Yelich of the premier’s office.

Advocates argue MZOs help boost the economy by expediting housing developments and large distribution warehouses, as demand has gone up.

But while there are clear winners when it comes to MZOs, there are also losers.

Among them: constituents shut out of an already complicated municipal planning process and local governments compelled to endorse incomplete development plans that will permanently re-shape their communities.

MZOs have also led to the destruction of farmland and environmentally sensitive lands razed for development projects never intended to be built there.

The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority said 16 MZOs have been approved on lands that are regulated and contain valleys, floodplains or wetlands.

The government says it has denied nine MZO requests that would have led to development on the Greenbelt. It would not say how many MZOs are now pending.

Phil Pothen, Ontario environment program manager for Environmental Defence, said the Ford government is using MZOs “to railroad municipalities into swallowing up huge amounts of farmland and natural heritage.”

Phil Pothen, Ontario environment program manager for Environmental Defence, said the Ford government is using minister's zoning orders "to railroad municipalities into swallowing up huge amounts of farmland and natural heritage." | Rene Johnston/Toronto Star

Vaughan Mayor Bevilacqua says it’s not surprising developers are pouncing on the opportunity to push their developments forward quickly.

“When you have a premier who is setting the tempo that ‘I want MZOs for economic development and the greater public good,’ then that is the ecosystem you are operating with…and people will access that ecosystem,” he said.

Torstar’s investigation raises questions about whether influence and connections play a role when it comes to accessing MZOs.

Take the case of Craft Development Corporation.

The company was granted an MZO on July 8, 2020 for a project in Lindsay that will include 500 homes and a 100,000-square-foot commercial building, long rumoured to be a Walmart.

The president of Craft Development is Carmine Nigro. Until two years ago, he was also vice-chair of the PC Ontario Fund, the party’s fundraising arm.

A year before the MZO was issued, Nigro was appointed chair of the LCBO by the Ford government.

Shortly after his LCBO appointment, according to a Globe and Mail story, Nigro helped organize a $1,000-a-person fundraiser for then-Finance Minister Vic Fedeli, who oversaw the LCBO at the time.

Nigro donated $9,930 to the Ontario PCs in the past four years, including $3,200 to Ford’s riding and 2018 leadership campaign. He donated $1,000 to the Liberals in 2014.

Nigro declined to comment.

Developers are also active donors at the municipal level of politics.

A 2010 study using data collected by York University political science professor Robert MacDermid found that nearly half of municipal election campaign donations for mayors and councillors in York, Peel, Durham and Halton regions came from the development industry.

In Vaughan, at least $120,000 was donated by developers and their family members to candidates in the last municipal election. In Markham, they donated at least $70,000.

“If someone gives you money, they are for sure expecting something in return,” said Markham Deputy Mayor Don Hamilton. “That’s just how it works.”

Getting an MZO from the Ford government has the appearance of a free-for-all.

“When other developers saw how these MZOs were being issued, they all wanted MZOs,” said Caledon Councillor Annette Groves, who has been critical of how the orders are being used.

A group wanting an MZO is expected to make a request to a local council, according to the process outlined by the ministry of municipal affairs. If the local council votes in favour, the request goes to the ministry and the minister makes a decision.

“We expect that municipalities have completed their due diligence, including consultation with local communities who will be impacted by the MZO, before a request is sent to the minister,” said Caputo, the minister’s spokesperson.

Beyond that, there is no defined process for a council to follow.

In this procedural grey zone, MZOs have to come to life in a patchwork of ways, often with municipalities figuring it out as they go.

In some municipalities, MZOs have been discussed at an open council meeting, while in other cases they have been discussed behind closed doors and then shared with the public.

Critics see them as a way for proponents to bypass much of the public process.

In Cambridge, a developer currently seeking an MZO for a one-million-square-foot warehouse preferred a zoning order so its project could be expedited and free from public scrutiny or potential appeals, according to a staff report.

Council unanimously endorsed the MZO request, without any public consultation. The MZO is awaiting provincial approval.

In at least four cases, there’s evidence the developer went over the head of the local council and straight to the province with an MZO request.

The mayor of New Tecumseth told the local newspaper the Ford government pressured his town’s council to make a quick decision on the MZO request that was ultimately granted to Flato Developments.

The MZO allows Flato to add nearly 1,000 residential units to the small community of Beeton, which has a current population of just 4,000.

Councillor Shira Harrison McIntyre, who voted against the MZO, said the project was “too big and too fast for Beeton,” while resident Sarah Marrs-Bruce said the small community already has problems with flooding “to the point that no further development was to be approved until that was addressed.”

Flato used the tactic twice more in the town of Whitchurch-Stouffville, when the company approached the council for two MZOs in 2020, including one for a residential and commercial hub atop environmentally sensitive land currently zoned “flood hazard.”

In both cases, just days or weeks after Flato’s applications for an MZO were submitted to the town for consideration, municipal staff received calls from the province asking for the council’s position, according to staff reports.

“Council took the position, (the province is) going to do it anyways,” said Stouffville Councillor Sue Sherban, who cast the only vote against both MZOs. “But then the minister took the position, ‘you approved it, so we will approve.’ So at the end of the day, both were trying to blame each other.”

Last year, Ontario’s NDP filed a complaint to the province’s integrity commissioner after a Chinese company, Xinyi, was granted an MZO in July 2020 to build a $400-million glass factory in Stratford.

The NDP alleged there had been extensive collaboration between Xinyi and the provincial government for two years prior to the MZO, including an off-the-books meeting between Ford and a Xinyi representative.

Facing a backlash from Stratford residents, Xinyi hired a former Ford government director of communications as a lobbyist.

The project died soon after, Xinyi suspended its planned factory and the province agreed to revoke the MZO.

“Misinformation and falsehoods spread by small opposition groups have negatively impacted public perception of the project,” Xinyi said in a statement. “Radical insinuations were made, with overt hostility demonstrated in opposition to the project’s development.

And in one case, the province enacted special legislation to ensure an MZO proceeds.

In November 2020, Ontario announced an MZO to fast-track a warehouse’s construction in Pickering’s wetlands, land normally prohibited from development.

Residents protested development on the Duffins Creek wetlands in Pickering. | Jason Liebregts/Metroland

The project would create more than 10,000 jobs, the province boasted. The developer behind the warehouse was associated with a subsidiary of Triple Group of Companies, owned by the Apostolopoulous family, who have donated nearly $36,000 to the PC Party and its candidates since 2014. They have also donated $55,000 to the Liberals, all of it prior to the PC party taking power in 2018.

A month after the MZO was issued, the province introduced legislation that forced local conservation authorities to permit development on environmentally sensitive land if it was part of a minister’s order.

When environmental groups challenged this law, the government tried to derail their case by retroactively changing the law through new legislation that said MZOs were not required to comply with what’s known as the provincial planning statement -- the rule book governing the province’s land use planning.

It was only when Amazon, the anticipated client for the proposed warehouse, publicly disclosed it would no longer consider the site, that the plans for the warehouse came to a standstill. Pickering council voted unanimously in late March to revoke part of an MZO.

Developers and local councils often talk about how proposed MZOs will help increase the stock of affordable housing and seniors housing.

But there is no way for a council to guarantee such promises will be kept once the province issues the order.

Vaughan Mayor Maurizio Bevilacqua (far right) holds a cheque aloft with developer Mario Cortelluci, whose family donated $3 million in 2018 to secure the naming rights for a new hospice facility. Bevilacqua said there is no connection between developers' donations and them receiving minister's zoning orders to fast-track developments. | Susie Kockerscheidt/Metroland

Vaughan Councillor Iafrate said that in one of the MZOs the Vaughan mayor brought forward in October -- a condo development near Keele St. and Bowes Rd. -- there was a requirement for 10 per cent affordable housing in the project. Given the shortage of such homes in the region, Iafrate, who also ran for the provincial Liberals in 2018, felt compelled to vote in favour of it.

When the MZO was issued by the province in March 2021 -- fast-tracking the project by three to five years -- she said there was no requirement for affordable housing in the minister’s order. “We can’t force it. We can negotiate, but that doesn’t mean they have to listen,” she said.

In a normal development process, before council will sign off on a project, builders are expected to provide studies analyzing potential impacts on the environment and local traffic, and hold public hearings. Details of the development are often negotiated before final approval is given.

But MZOs don’t have the same requirements.

The only material supporting one MZO request brought forward by Vaughan’s mayor was a map and a three-page letter, written by the Cortellucci family’s Cortel Group.

Eight days later, Vaughan endorsed the request to fast-track the development of a 20-acre parcel of land at the corner of Jane St. and Rutherford Rd. The council resolution was longer than the Cortel Group’s request letter.

And just 16 days after that, on Nov. 6, the province issued the MZO, green-lighting the high-rise development.

With the MZO floodgates open, there is a growing ire among developers who have applied through the standard zoning process, which can take several years and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. At least one developer, Solmar, tried to bring its own MZO request to Vaughan council, but no politician would back it, saying they didn’t know enough about the project to do so.

Vaughan councillors have asked staff to come up with a policy on how to deal with MZOs.

“The province does not take the time to look at each request from a planning process, they are looking at a higher level,” said Vaughan Councillor Yeung Racco, who ran for the provincial Liberals in 2014. “What that criteria is...we don’t really know. And that’s a problem.”

Racco said she voted against two of the three MZO requests the mayor put forward, only voting for the one that was adjacent to a development that had previously received a MZO. “I did so, because I believe in fairness.”

She said that the planning process needs to be independent of relationships.

“I will not say because you are a friend, I will treat you better than somebody else. I will always look at it from a planning perspective: does it make sense, is it going to help this community, is it going to add to our community?”