In the dark: The cost of Canada’s data deficit

When it comes to basic data about its own citizens – from divorce rates to driving patterns to labour trends – Canada simply doesn’t have the answers. If information is power, this country has a big problem. Eric Andrew-Gee and Tavia Grant report

Theglobeandmail.com

Jan 27, 2019

Eric Andrew-Gee and Tavia Grant

Two months after Donald Trump was sworn in as U.S. President, a couple of Princeton economists published a research paper that accidentally suggested a reason why.

The findings showed something shocking about a core part of Mr. Trump’s voter base: White, middle-aged Americans, especially those without a college degree, were dying at a rising pace.

This kind of thing is not supposed to happen in industrialized societies. Mortality rates have been declining for decades in comparable rich countries, and even for blacks and Hispanics in the United States. Most disturbing of all, the phenomenon was being driven by what the two economists called “deaths of despair” – those caused by drugs, alcohol and suicide. The white working class was literally poisoning itself to death.

Naturally, researchers in other countries began to wonder if the same thing was happening in their backyards. In Canada, one of those people was Arjumand Siddiqi, a public-health scholar at the University of Toronto with an impressive résumé that includes a doctorate from Harvard and a co-appointment at the University of North Carolina. If anyone was going to replicate the study in Canada, and find out if working-class white Canadians were dying at a growing rate, it was her.

So, Prof. Siddiqi set out to do just that. What she found, though, was that she couldn’t. The numbers weren’t there. In Canada, death records – which Princeton professors Angus Deaton and Anne Case had used – do not tell you the person’s race and education level.

Prof. Siddiqi had to get creative. She put in a request with Statistics Canada, asking it for access to a database that links national mortality numbers with census results. Statscan agreed, but made the linked data available for only three census years – 1991, 1996, and 2001 – which wouldn’t give a picture of the whole population annually and over time. And it was the whole U.S. population, annually and over time, that Profs. Deaton and Case were looking at.

“That was when we realized that, ‘Wow, we just went through all of that and we can’t get the data,’ ” Prof. Siddiqi says.

In the end, she gave up. Our nearest neighbour was experiencing an unprecedented social crisis – one with the apparent power to reshape American society in dramatic ways – and there was no clear way to find out if the same thing was happening in Canada. She remembers feeling both disappointment and frustration: “It was like, ‘Here we go again.’ ” This wasn’t the first time Prof. Siddiqi had run into gaps in Canadian public data.

And she wasn’t alone. At a time when distorted numbers ricochet around the Internet at the speed of a 4G connection, reliable, accessible data about our society is more valuable than ever. And yet, in fields ranging from public health to energy economics to the labour force to the status of children with disabilities, there’s a lot that Canada simply doesn’t know about itself.

Consider that we don’t have a clear national picture of the vaccination rate in particular towns and cities. We don’t know the Canadian marriage or divorce rate. We don’t know how much drug makers pay the Canadian doctors who are charged with prescribing their products. We don’t have detailed data on the level of lead in Canadian children’s blood. We don’t know the rate at which Canadian workers get injured. We don’t know the number of people who are evicted from their homes. We don’t even know how far Canadians drive – a seeming bit of trivia that can tell us about an economy’s animal spirits, as well as the bite that green policies are having.

Our ignorance is decades in the making, with causes that cut to the heart of Canada’s identity as a country: provincial responsibility for health and education that keeps important information stuck in silos and provides little incentive for provinces to keep easily comparable numbers about themselves; a zeal for protecting personal privacy on the part of our statistical authorities that shades into paranoia; a level of complacency about the scale of our problems that keeps us from demanding transparency and action from government; and a squeamishness about race and class that prevents us from finding out all we could about disparities between the privileged and the poor.

But if the problem has deep roots, it has never mattered more. We live in a data-driven age, when the internet and the processing power of computers has made it easier than ever to hoover up statistics about a society, make them public and accessible, and crowdsource better decisions about how to deliver everything from income support to green incentives to job training. Governments around the world have harnessed that power to make themselves smarter, leaner and more effective.

In 1941, Winston Churchill remarked on the value of government statistics: The “utmost confusion is caused when people argue on different numbers,” he said. In Canada, we are often arguing without any numbers at all.

While the federal government has made some progress on the file, a months-long investigation by The Globe and Mail has shown that Canada still has a long way to go. Interviews with dozens of academics, current and former government officials, businesspeople and non-profit executives – along with an analysis of Statscan surveys and an examination of data regimes around the world – have identified scores of serious gaps. These stifle business innovation, keep patients in the dark, leave the government guessing about whether its policies work and prevent Canadians from understanding core challenges facing the country.

“We have high-quality data – when they produce it,” says Robert Andersen, a professor of political science, sociology and statistics at the University of Western Ontario who frequently makes use of Statscan numbers. Aside from the patchwork nature of the numbers we collect, meanwhile, “it’s increasingly hard to get access to some of that data.”

That means we’re missing an untold number of warning flags about the problems facing Canadians – problems we don’t know about and so can’t properly address. It means that, on a staggering range of issues, Canada and its leaders are flying blind.

James Cortada is a historian of information. In 38 years working at IBM, and in some 50 published books, he has become an internationally recognized expert on the power of government data to improve people’s lives. “There has to be a philosophy – a cultural philosophy and political philosophy – that sharing information helps society,” the University of Minnesota senior research fellow says. “Without that glue, you cannot get anything done.”

He gives an example: About four million men joined the U.S. armed forces during the First World War and each of them was meticulously measured and weighed. This taught the federal government that most men came in a few standard sizes: for example, 34 waist, 15 neck, 40 chest. That information allowed the military to mass-produce uniforms that would more or less fit each of its recruits, allowing them to move comfortably in the field of battle while saving a small fortune on excess fabric. As an added benefit, the sizes became garment-industry standard after the war. Not world-changing stuff on its face. But properly outfitting a victorious army, saving the government untold millions of dollars and making a key industry more efficient isn’t a bad spot of work for a few numbers jotted down on a chart.

“You can find examples like this in health, in education, in the military, across industries, in every decade,” says Prof. Cortada. “You’ve got to figure out what’s the target, what’s the problem. For that, you need information.”

The fancy word for information, data, has been dragged through the mud a bit lately. Thanks to the likes of Facebook and Google, it’s now often associated with the personal information that companies scrape – from your online behaviour, your likes and dislikes, and your computer searches – and then sell to advertisers. It’s an intrusive process that has generated an understandable backlash about privacy, sometimes even directed at official statistical bodies.

But government data are a different thing. It’s the information that various ministries, agencies and bureaus collect about citizens through administrative sources – such as tax filings and birth records – and questionnaires such as the census and community surveys. And unlike the tech companies that probe our digital lives for profit, governments aren’t in the business of caring what the numbers say about us individually: They’re looking for patterns.

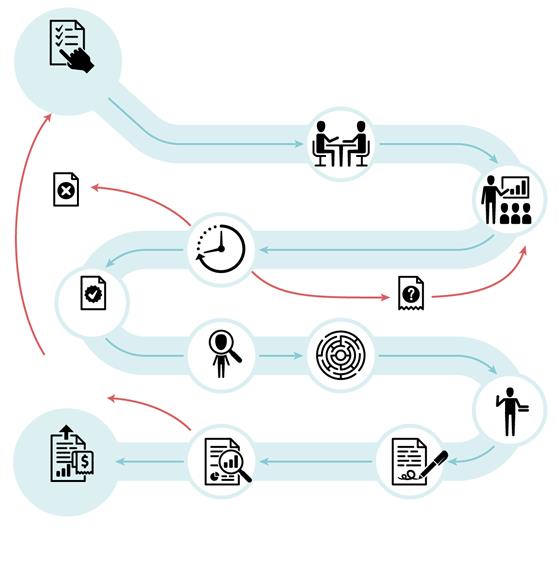

The best way to spot trends is to enlist the public’s help by making your data open. At its best, this produces a charmed cycle: The government collects numbers, makes them anonymous and puts them on a website; a researcher, or even an ordinary citizen, notices something in the numbers (a spike in deaths! or a decline in productivity!); the government hears the alarm and can begin figuring out ways to address the problem.

This kind of cycle is never more valuable than when it involves health data. Sometimes it saves lives. In the early 2000s, an arthritis drug called Vioxx was being hailed by North American doctors and patients for reducing inflammation and pain with fewer side effects than those caused by similar drugs. But the Therapeutics Initiative, an independent group of researchers at the University of British Columbia, was among the first to raise a red flag: Vioxx users also seemed to have a higher risk of heart attack, among other health problems.

Using clinical-trial data collected by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the group wrote up its findings in a newsletter aimed at B.C. doctors. Armed with that sobering information – and aided as well by a provincial pharma plan that limited access to the drug – the province’s doctors subsequently wrote relatively few per-capita prescriptions for Vioxx and similar medications, even while such prescriptions skyrocketed in Ontario. It would later emerge that the drug may have been linked to more than 60,000 deaths in Canada and the United States before being pulled from the market in 2004.

“It feels really good to be able to say we think we reduced the number of people who died of heart attacks in British Columbia because we were able to find and convey data on the danger of these drugs to prescribers,” says researcher Alan Cassels, now deputy editor of the Therapeutics Initiative newsletter.

In Canada, though, this cycle too often breaks down. Either the government hasn’t collected the relevant numbers or it won’t make them public. Important questions go unanswered. That’s especially dangerous for Canadian patients: Our health-care system is pockmarked with data gaps that leave people unsure of the quality and integrity of the care they’re getting, and leaves us in the dark about whether the system is meeting people’s needs.

Nav Persaud is a Toronto family physician who sees lots of pregnant women struggling with morning sickness. About a decade ago, he regularly prescribed the drug Diclectin for the nausea and vomiting that can come with the early weeks of pregnancy. But then he started noticing that the drug wasn’t having much of an effect. So he asked Health Canada for the clinical-trial data it had about Diclectin – information the manufacturer submits to get approval for a new drug.

Health Canada said no, calling it “confidential business information.” Unlike the United States and Europe, Canada doesn’t automatically make clinical-trial data available. “In Canada, you have to do what we did: You make a Freedom of Information request, and then you count down the years until the request is fulfilled,” Dr. Persaud says. “If you’re vomiting during pregnancy, you don’t want to get the information five years later.”

What he finally learned by reviewing data from the drug trials, and was able to publish in early 2018, is that Diclectin doesn’t work nearly as well as its maker, Quebec-based Duchesnay Inc., claimed. In one key trial, he found that the drug had barely outperformed a placebo. He no longer prescribes it.

Last spring, Health Canada finally committed to making clinical-trial data more publicly accessible; it plans to publish new regulations concerning that decision this spring. But full proactive disclosure of clinical information for new drugs and medical devices isn’t expected to be the law of the land until 2021 at the earliest.

“Health Canada has no sense of urgency whatsoever,” says Terence Young, chair of the advocacy group Drug Safety Canada. “It’s like it’s happening on a different planet.”

Mr. Young’s sense of urgency is fuelled by personal tragedy. In 2000, his 15-year-old daughter, Vanessa, died of a heart attack after taking the digestion drug Prepulsid. Only later did he learn that eight small children had also died during trials for the drug.

Mr. Young says “there is no doubt” he and his wife would have studied the clinical data if Health Canada had published it, and adjusted their daughter’s treatment accordingly. “Gloria and I were very careful parents,” he says. “There’s no chance we would have let Vanessa take that drug if we knew anyone had died after taking it.” But in 2000, and still today, the gap in clinical-trial data means that even careful parents are left in the dark about a key aspect of their children’s health.

Canada’s data hole about the condition of people with disabilities is just as galling.

“If you’ve got a child with a developmental disability, you want to know where to move,” says Cameron Crawford, a disability-studies instructor at Ryerson University in Toronto. “Right now, good luck.”

Provinces gather their own information, but each province tracks different things, and with different degrees of care. There is no regular, national comparison of what programs and funding are available for children with disabilities – or of their life outcomes, such as whether they finish school. We don’t know how many young people participate in special education in each province, or how many teachers have the training to provide it, or the amount of special-education funding in each province, in total or per student.

“This kind of information, if available at all, tends to be squirrelled away in various departmental and program reports and budget data across the provinces and territories, and isn’t comparable across jurisdictions,” Prof. Crawford says.

Rachel Martens has experienced the fallout. She lives in Calgary with her 12-year-old son, Luke, who has a rare chromosome disorder as well as autism and cerebral palsy. But a lack of data hurts her efforts to seek out access to health care, to learn about supports available to families and to find recreational programs that children such as Luke can participate in. “A lack of information for families,” she says, “takes an emotional toll.”

Prof. Crawford has always found these gaps puzzling, especially because the United States has such rich data of this kind. He points, for example, to a voluntary collaboration between states called the National Core Indicators, which provides a fairly comprehensive comparison of the condition of people with developmental disabilities, far beyond anything Canada offers.

“People become captive to where they are and what they’ve got; that’s a function of the programming but also the information about the programs,” Prof. Crawford says.

The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) was created in 1994 to help break down these kinds of provincial silos. Independent and not-for-profit, it collates and publishes health data from the provinces on everything from hospital wait times to alcohol abuse. It has done significant work in the past 25 years, especially in bringing together a national picture of the opioid-overdose crisis.

But the CIHI can only do so much. Disability, for example, falls outside its mandate. And the organization has no power to force provinces to provide data they would rather not share.

Sometimes, of course, provinces have every incentive to keep data hidden, notes Katherine Fierlbeck, a professor of political science at Dalhousie University who studies Canadian health care. For those at the bottom of the pack, data can be damning. “If you're performing badly relative to other provinces, why would you want to help people point that out?” she asks.

Data locked in provincial silos hurts health-care businesses, too. Stuart Feldman heads the Canadian operations for PointClickCare, a Mississauga-based tech company that provides electronic health records for long-term care homes in Canada and the United States. It has seen explosive growth since launching in 2000, and now handles more than 2.5 million health records a day. About a tenth of those are in Canada, but virtually none are in Quebec. PointClickCare has been reluctant to move into Canada’s second-biggest province, in part because the company doesn’t know how many long-term care homes exist there.

Without a firmer handle on the market, Mr. Feldman can’t sell his bosses on a costly expansion. “I could tell you there’s roughly 500 nursing homes in Quebec, but I could not tell you whether that’s accurate or not.”

As of 2013, when Statistics Canada launched its most recent survey on the number of long-term care homes in Canada, Quebec did not participate. It still does not send the number to CIHI, citing provincial authority over health care. When asked by The Globe, the Quebec health ministry did, in fact, reveal that there were 453 long-term care homes within its borders – but hastened to point out that its definition of such facilities may differ from that used by other provinces.

That lack of common definition means Mr. Feldman’s estimates about the size of his potential market are “written in pencil” – not just in Quebec but across the country. “If I needed to, today, give my executives a report on how many long-term care homes there are across Canada, I could not provide them that report,” he says.

That’s a problem not just for PointClickCare but also for its competitors in the growing e-health and senior-care sectors. It also means it’s hard to tell which provinces are providing adequate facilities to the elderly, and which aren’t. “There’s a lot of things where you’re scratching your head,” says Mr. Feldman. “How do we not know this basic information?”

No one asks themselves that question more often than academics. They are patient zero for Canada’s data-gaps epidemic. And the frustration they experience has implications for us all: When scholars work without access to proper data, they are unable to tell us stories about our world and ourselves that can only be unearthed when expert analysis is applied to a thorough rendering of the raw facts.

Lindsay Tedds, a professor of economic policy at the University of Calgary, has been struck recently by the difference, between the United States and Canada, regarding one of the most fundamental subsets of demographic data: birth records.

To begin with, the standard U.S. certificate of live birth collects all kinds of detailed information about the child’s parents – particularly their level of education and their race. “We know that African-American women die in childbirth at an alarming rate. We know that non-white babies are born smaller and earlier,” says Prof. Tedds. “Both of these factors are highly related to [the] poverty of the parents.” In Canada the picture is far less clear. “Imagine,” she says, “if we had similar detailed, population-level data, including for pregnancy and birth outcomes, for Indigenous moms.”

But even if the records were more detailed, she notes, the information would be harder to dig out: “The United States birth data, you just go onto a website and download it.”

In Canada, by contrast, birth data are kept in a series of facilities called Research Data Centres – the bane of many researchers trying to unlock tricky problems in Canadian social science. Statistics Canada opened the first RDC in 2000, with the aim of giving researchers access to so-called confidential microdata – the previously hidden guts of Statscan’s collections, such as census responses, health-survey results and birth records – without compromising anyone’s privacy.

But while they contain a rich trove of data, the fact that it is embedded with potentially identifying details about individual Canadians – not names, which are scrubbed ahead of time, but occupation and gender, for example – means that researchers must jump through a series of bureaucratic hoops before they can get their hands on it. Wendy Watkins, a Carleton University sociologist and former Statscan analyst, calls the centres “little data jails.”

There are 30 RDCs across Canada, almost all on university campuses – although Brandon, Sudbury, Trois-Rivières, Charlottetown and Peterborough, Ont., all university towns, have no such research centres. There are no RDCs at all in Nunavut, Yukon or Prince Edward Island. Because researchers have to visit them in person, that often means travelling hundreds of kilometres.

And that journey only gets them to the jailhouse gates. Then the real hurdles emerge. These can include providing a five-year address history, submitting a research proposal well ahead of time, and being formally sworn in as a government employee for the duration of your visit, complete with a legally binding oath of secrecy. If you are not a graduate student or university faculty, you’re likely to face more than a dozen steps before being able to actually publish your research. In some cases, researchers have to pay a sizable fee – routinely more than $5,000 – to access the information.

“I had to get fingerprinted,” says Prof. Andersen of Western, “even though I had my passport. What did they think, I was faking my passport?”

In other countries, the kind of data we keep cloistered in RDCs for privacy reasons is often simply scrubbed of identifying details and opened to the public. Says Calgary’s Prof. Tedds, “We know enough about how to censor and anonymize data that those concerns … they shouldn’t be concerns.”

Placing the burden of security onto individual researchers, in turn, means that reams of information, painstakingly gathered by our government and waiting to be sorted, distilled and interpreted – and, possibly, put to use improving Canadian lives – remain untapped. “I’ve had a few colleagues tell me they don’t study Canada because it’s too much of a pain in the neck,” Prof. Siddiqi says. “Of course I also want to study Canada, but at a certain point you have to throw your hands up.”

The recent controversy over Statscan’s plan to request customers’ personal financial data from Canadian banks might have given the impression of an outfit with a cavalier attitude toward privacy. In fact, the episode was deeply out of character for the agency. Typically, Statscan suffers from the inverse problem, what former assistant chief statistician Michael Wolfson calls “excessive privacy chill.”

When the public doesn’t have data – either because of overcaution or, simply, funding shortfalls – the whole policy-making process can break down.

In recent years, for instance, Ottawa and the provinces have rolled out a suite of environmental programs meant to cut greenhouse-gas emissions. Those include a federal carbon tax, electric-car incentives, higher fuel-efficiency standards and grants for renewable-energy firms. In each of these cases, though, we lack the public data to fully understand if the policies are working.

The monthly Statscan numbers on provincial gasoline sales are full of holes, for example: Newfoundland and Labrador’s numbers for the first half of 2017 are missing, while Nova Scotia’s numbers contain several months-long gaps in the past three years. The agency will not say why. (“Statistics Canada does not disclose the parameters and rules used to control disclosure,” the agency said in an e-mail). But that hiccup in the data could soon leave us in the dark about how the East Coast is adapting to a federal price on carbon.

What happens when Canadian drivers do gas up is an even bigger mystery. Simply put, “We don’t have data on how far people are driving,” says Nicholas Rivers, Canada Research Chair in climate and energy policy at the University of Ottawa.

Statscan used to ask a sample of Canadian motorists to write up their car trips in travel diaries, but stopped doing so in 2009 due to a low response rate and budget constraints. Later, the agency got another sample of drivers to put trackers in their cars that would tally the distance they covered, but Statscan soon discontinued that project, too – again because of “budget decisions.” Transport Canada, meanwhile, cancelled a similar, short-lived program in 2016. As a result, we haven’t had any driving data since 2015.

That might not matter as much if Canadians were driving more Teslas and Priuses. But sales numbers of electric vehicles are hard to come by: Transport Canada collects them for “research purposes only” – they have the data, but won’t publish it. Meanwhile, the most recent auto-emissions-compliance report from Environment and Climate Change Canada contains some data about electric-vehicle sales, but only up to 2016.

The secrecy, bureaucracy and plain eccentricity that have come to characterize the country’s central data-gathering agency are far from unique among federal departments and ministries. Almost every one of them gathers and publishes its own significant stores of data – and Canada’s Auditor-General has spent years quietly pointing out how badly they tend to manage the task.

Glenn Wheeler, a principal in the federal watchdog’s office, says ministries often don’t gather enough data about their own policies to have a good sense of whether those policies are working – or don’t release enough data to convince the public, which is paying for the programs through tax dollars. “It’s a serious issue we find across our audits, across departments, across a number of years,” he says.

What Mr. Wheeler doesn’t mention, but is hard not to notice, is the number of data gaps that threaten to undermine policies the government of Justin Trudeau has put a lot of stock in – policies meant to address such issues as sexual abuse, the settlement of refugees and improving the lot of Indigenous Canadians. “Good policy is impossible without good data,” said Finance Minister Bill Morneau in a 2016 speech. But this government’s trademark policies often don’t have good data behind them.

In an audit of the Canadian Armed Forces released last fall, the auditor-general found that the military had “no centralized system to collect and track incidents of inappropriate sexual behaviour in a systematic way,” despite launching Operation Honour to combat sexual misconduct in its ranks in 2015. An Armed Forces spokesperson told The Globe that the military is now addressing the issue: a sexual-misconduct tracking system was “implemented” this past October and it will be “fully operational” some time in 2019.

Meanwhile, a 2017 study of the government’s efforts to settle Syrian refugees – one of the Trudeau government’s signature initiatives – found that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada was not gathering numbers on such key measures as the average number of months those refugees spent on income assistance, the effectiveness of the language training they have received, or the percentage of refugee children attending school.

Or take, for example, the issue of education and job training for Indigenous people, a population with labour-force-participation and postsecondary-completion rates lower than that of other Canadians. Last year, the auditor-general found that Indigenous Services Canada was drastically underreporting the high-school dropout rate for on-reserve First Nations students – counting only those who dropped out in their final year, not those who left school even earlier, between Grades 9 and 11. Between 2011 and 2016, the department falsely reported that almost half of those students were finishing high school; in fact, it was closer to one-quarter.

The auditor-general also found that Employment and Social Development Canada, a department that runs job-training programs to help vulnerable populations find “sustainable and meaningful work,” knew almost nothing about the nature of the jobs its Indigenous clients were getting – including whether those jobs were part-time or full-time, or how long people stayed in them. As a result, the government had only a tenuous handle on whether the programs were working.

“If you don’t have good information or data on the performance of a program, it’s difficult to monitor it,” notes Mr. Wheeler. What’s more, he points out, there’s no way to answer a key question: “ ‘Do we increase funding or reduce funding?’ ”

Of course, government data aren’t all about dollars and cents. The information can save lives and alleviate the misery of people living in the shadows. Even so, if you care to look at public data as an investment, it winds up being a pretty good one.

New Zealand, for example, has estimated that every dollar it spends on its census generates a net benefit of at least five dollars in the national economy, in part by allowing the government to better target funding for health care and for programs aimed at improving outcomes for Indigenous citizens. In Britain, a 2013 report by the accountancy firm Deloitte estimated that the data held by the public sector in that country – and released for use and reuse – were worth more than $8.5-billion a year, thanks, in part, to its value in holding government to account and in spurring innovation in the economy.

As the benefits of open government data become more widely accepted, Canada is falling behind many of its peer countries in making use of the stuff. Ireland publishes a comprehensive biennial data set on the well-being of children; Denmark tracks every aspect of gender equality; Britain breaks down many social-welfare indicators by ethnicity; and Australia publishes national workplace-injury rates – none of which can be said of Canada.

But no country throws our data failures into starker relief than does the United States. You might expect our southern neighbours to be data laggards: After all, theirs is a country that tends to prefer small government and emphasize individual rights over the common good.

Instead, Americans are world leaders at gathering and sharing an abundance of national numbers. "The U.S. has awesome data on almost everything,” says Jennifer Winter, director of energy and the environment at the University of Calgary school of public policy.

Some attribute U.S. public-data excellence to the country’s (small-r) republican form of government, which treats government property as the people’s. But it’s not just a question of national DNA. The United States has made strides in recent years as a result of deliberate government policy.

In 2013, then-president Barack Obama signed an executive order making government data open and machine-readable by default – a move which, remarkably, Donald Trump signed into law just this month after being presented with a bipartisan bill giving Congressional approval to the broad strokes of president Obama’s order.

During his tenure, Mr. Obama also hired Silicon Valley whiz D.J. Patil as the country’s chief data scientist. Mr. Patil’s marching orders: to free up more of the information that had been mouldering, unseen and unused, in federal government vaults. He realized, in short, that the country could solve more of its problems if it had more eyeballs trying to identify them. “Through these data sets, you get brilliant insights,” he says. “We’re harnessing the power of the country's entire knowledge base.”

Embedded in Mr. Obama’s health-care law, meanwhile, was a sunshine list for payments made by drug companies to doctors. The data helped reveal some chastening facts. Among them: The more money the average doctor receives from opioid makers, the likelier she is to prescribe opioids; and even such small gifts as a single meal tend to tilt doctors toward prescribing more expensive brand-name drugs.

That analysis would not be possible in Canada; the numbers aren’t there. (Under its previous Liberal government, Ontario was on the verge of forcing pharma-payment disclosure, but the program has been put on hold by Doug Ford’s Conservatives.)

A disarming number of people who have spent time thinking about the problem come to the same conclusion about why this is: Yes, federalism creates data silos, and yes, Statscan is too risk-averse and cash poor, and yes, provinces and federal departments have a built-in incentive to keep their failures hidden with data blackouts. But maybe, just maybe, the problem has even deeper cultural roots. Maybe we’re just not curious enough about what goes on within our borders – blissful in our ignorance. Maybe, these people suggest, the problem comes down to Canadian complacency.

Tellingly, Canada’s Copyright Act, signed in 1921, gave the Crown the rights, for a full 50 years, to any work produced by any government department – a stark contrast with our southern neighbour, which banned government copyright in the 19th century. “The U.S., in its early history, made legislation that said, ‘We shall make this information available to the people,’ ” says Mark Leggott, executive director of Research Data Canada, a non-profit that helps researchers use public data. “In Canada, we made it so that the information was the property of the Queen.”

Craig McKie, a retired Statscan analyst, nods to that era when trying to understand why he was ordered to destroy valuable data sets while at the agency. “Canada started as a colony without an independent government,” he says. “The conception was, ‘Nothing important happens in Canada. All the important things happen somewhere else. So why would you care?’ ”

Mr. Young of Drug Safety Canada muses about cultural complacency when he tries to figure out why Canada is always “the tail behind the dog” in demanding transparency about something as basic as the safety of pharmaceuticals. “Perhaps it’s because we’re too trusting,” he says. “We feel that we have a society that’s less influenced by commerce, and a more caring society.”

Prof. Siddiqi, the health researcher at the U of T, talks along similar lines when it comes to our aversion to tracking the well-being of particular racial groups. “Somehow,” she says, “we’ve convinced ourselves that these are American problems, and these are not our struggles.”

It doesn’t have to be this way. The Liberals’ 2015 election platform promised to “embrace open data” and stated that a Liberal government would “make government data available digitally, so that Canadians can easily access and use it.”

And, to be fair, the Trudeau government has certainly made some progress over the past three years. Most famously, it reinstated the mandatory long-form census, which Stephen Harper’s Conservatives had axed in 2010.

A spokesperson for Jane Philpott, the minister of digital government, a portfolio recently created and tacked on to the Treasury Board, also noted that 81,909 data sets are available through the federal open-government portal (though many of those were published by previous governments). Anyone can now open their laptop and look up everything from Canada’s sulphur-oxide emissions, over time, to the country’s “spatial density of oats cultivation.”

Like the governments of every industrialized country, Canada posts far more data online than anyone would have thought possible 30 years ago. It actually tied for first with Britain in a recent “open-data barometer” created by the World Wide Web Foundation (though it’s worth noting that the ranking awards points for fairly basic achievements, like publishing government budgets and election results, and that Canada scored poorly on national environmental statistics).

Statistics Canada would like you to know that it is making progress, too. Anil Arora, the agency’s chief statistician, points to new technologies and techniques that are changing the way it collects public data. Last year, for instance, the agency crowdsourced black-market cannabis prices by asking the public to use an app called StatsCannabis. More than 20,000 people responded. Statscan is also experimenting with “virtual data research centres” that will make microdata more easily accessible by computer, although their inauguration is likely years away.

Notwithstanding the backlash to Statscan’s banking-information scheme – and anxiety in some quarters about giving government more power to gather the personal information of citizens – the public has also shown signs of embracing the value of government data in recent years. The cancellation of the 2011 mandatory long-form census had the unexpected consequence of raising the census’s profile, and maybe even its popularity. The 2016 response rate was the highest ever, at 98.4 per cent, suggesting that Canadians see taking part in data collection as their civic duty, provided their confidentiality is protected and they feel it’s for the public good.

To be sure, a problem as vast and diffuse as a country’s ignorance about itself can hardly be laid neatly at one government’s door, much less one ministry’s. Still, given the Liberals’ enthusiasm for evidence and openness, their reluctance to frankly admit that Canada has a data deficit and to propose concrete solutions is notable.

When asked to comment for this story, the Prime Minister’s Office deferred to the minister of digital government, whose spokesperson’s answers focused on the government’s achievements, especially relative to the Harper Conservatives, and who spoke in general terms about plans for more data openness in the future. For example, in response to a question about the dozens of data gaps identified by The Globe, the spokesperson replied, “We have reinstated the long-form census, unmuzzled government scientists, and made ministerial mandate letters public while tracking progress on those commitments to Canadians. We know there is always more work to do."

The leaders of Statscan were also reluctant to take ownership of Canada’s data-gap problem. In an interview last year, Mr. Arora pointed a finger at academic researchers who are unable to ferret out the numbers they need. “I would argue that there’s still a lot of data that we have that either researchers don’t even know about or underutilize,” he said. “They find the vetting steps, the confidentiality component, to be a little too much for them.”

In the meantime, Canadian public data remains full of lapses, hesitations and holes – for things as basic as average wait times for mental-health services and the number of homeless people who die on our streets. And the data we have is often so hard to access, it might as well be hidden. Even Mr. Arora knows the dangers of asking the country to fly blind this way: “There could come a day when the population says, ‘You had access to all of these data stores and you could have reasonably used it to prevent something nasty from happening. Why didn’t you?’ ”

Mr. Arora posed his question as a hypothetical – but didn’t need to. Every day, Canadian governments have the chance to prevent nasty things from happening, by putting stark numbers in front of Canadians, so that the public can demand change where it’s needed and build on what the country is doing right. And every day, governments pass up the opportunity to do so. On maternal health, on Indigenous education, on environmental action, on the safety of drugs and the integrity of the doctors who prescribe them, on matters as seemingly mundane as how far Canadians drive and as patently urgent as the rate at which whole demographic groups are dying, governments deprive Canadians of the data needed to make good decisions. Every day, they leave Canadians in the dark.