Here are the four elements of a cyclist-friendly ‘protected intersection’

Thestar.com

June 18, 2018

Gilbert Ngabo

Amid efforts to eliminate preventable fatalities on Toronto’s streets, safety advocates are proposing a four-point plan to make the city’s intersections safer for cyclists.

In urban planning circles, intersections that are designed expressly to give cyclists more visibility and protect them from car traffic are known as “protected intersections.” They’re already popular in European cities where cycling culture is strong.

Implementing them is here the next logical step for Toronto, a city that has seen its fair share of road fatalities and collisions over many years, said urban designer Ken Greenberg.

“Council has to accept that this is a crisis,” he said. “We are still in a kind of denial.”

Greenberg previously spent over three years working as an urban consultant for the city of Amsterdam, where he saw firsthand the impact of protected intersections. He said such intersections are designed based on “practical science” and play a vital role in reducing anxiety and uncertainty for road users.

He said protected intersections don’t require any extra space, and offer the added benefit of making cycling more appealing. Cities like Montreal, Vancouver and Seattle have started implementing the model, proving “it can be done” in North America, he said.

According to the Toronto Centre for Active Transportation (TCAT), bike lanes in many Canadian cities simply disappear at intersections, which leaves cyclists in danger. A study conducted in the Vancouver area in 2015 showed the majority of collisions involving cyclists happen within intersections.

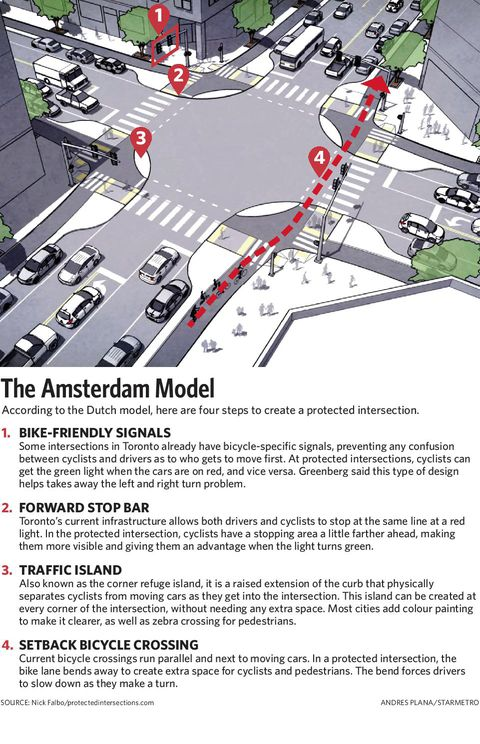

Here are the four components of a protected intersection, according to the Dutch model:

Traffic Island:

Also known as the corner refuge island, it is an extension of the curb that physically separates cyclists from moving cars as they get into the intersection. This island can be created at every corner of the intersection, without needing any extra space. Most cities add colour painting on the bicycle path to make it a lot clearer, as well as zebra crossing for pedestrians.

Forward Stop Bar:

Toronto’s current infrastructure allows both car drivers and cyclists to stop at the same line when they get to a red light. In the protected intersection, cyclists have a stopping area a little farther ahead, making them more visible and giving them an advantage when the light turns green. Cyclists looking to make a left turn can also use this space as they wait.

Setback Bicycle Crossing:

Similarly, current bicycle crossing runs parallel and next to moving cars. In a protected intersection, the bike lane slightly bends away in a manner that creates extra space for cyclists and pedestrians. Due to this bend, drivers are forced to slow down as they make the turns, which makes cyclists get out of their blind spots ahead of time.

Bike-Friendly Signals:

Some intersections in Toronto already have bicycle-specific signals, preventing any confusion between cyclists and car drivers as to who gets to move first. At protected intersections, cyclists can get the green light when the cars are on red, and vice versa. Greenberg said this type of design helps avoid the conflict in movement and completely takes away the left and right turn problem.