The high cost of low corporate taxes

A deep dive into the financial statements of Canada’s biggest corporations shows these companies pay far less than the official corporate tax rate.

Thestar.com

Marco Chown Oved

Toby A.A. Heaps

Michael Yow

Dec. 14, 2017

or every dollar corporations pay to the Canadian government in income tax, people pay $3.50. The proportion of the public budget funded by personal income taxes has never been greater.

At a time when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has made tax fairness a centrepiece of his government, the Toronto Star and Corporate Knights magazine spent six months poring over tax data to determine how much income tax corporations are really paying.

We found the amount of tax most big companies pay has been dropping as a proportion of their profits for years, and not only because the corporate tax rate has been cut repeatedly. Canada’s largest corporations use complex techniques and tax loopholes to reduce their taxes significantly below the official corporate tax rate set by the government.

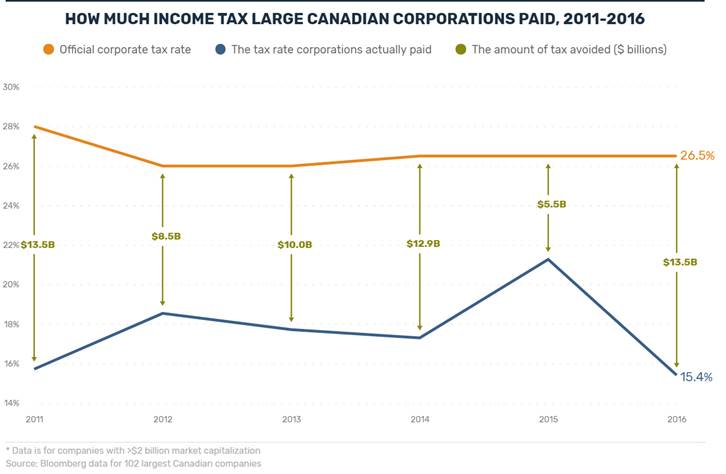

Our analysis of the financial filings of Canada’s 102 biggest corporations shows these companies have avoided paying $62.9 billion in income taxes over the past six years.

The 2011-2016 audited financial statements of all large Canadian corporations (those worth more than $2 billion) reveal they paid an average of 17.7 per cent tax.

During that time, the average official corporate tax rate in Canada for this group of companies was 26.6 per cent.

That 8.9 per cent gap translates into tens of billions of dollars that could have been used to pay for the schools, roads, hospitals, police and paramedics we all rely on.

The accounting manoeuvres Canadian corporations perform to reduce their tax bills are legal. But complex reporting rules make it difficult to determine if a company is actually paying its fair share of taxes.

The Star/Corporate Knights analysis looked at the amount of taxes companies paid as a per cent of profits over a six-year period to even out yearly fluctuations. Big losses and investments happen, and may reduce a corporation’s tax rates in any given year, but consistently low tax rates can indicate a pattern of avoidance.

This project is the first comprehensive attempt to combine Canadian corporations’ audited financial statements with government data to quantify the extent of corporate tax avoidance and determine how much it costs the rest of us.

“Some income simply is not taxed,” said Peter Spiro, an economist with the Mowat Centre, a public policy think tank at the University of Toronto. “The public policy question becomes: are these tax breaks or tax exemptions justifiable?”

At a time when stocks and corporate profits are near record highs, the federal government has targeted small private corporations, expecting to recoup an estimated $250 million in tax revenue by closing loopholes.

If Ottawa instead closed all the loopholes used by large corporations, it could collect 40 times more than that.

In an average year, the 102 biggest companies in Canada pay $10.5 billion less than they would if they paid tax at the official corporate tax rate.

“That gap is undermining the integrity of the tax system,” said Jordan Brennan, an economist with UNIFOR, Canada’s largest private sector union, which represents Star employees. “Once we establish what the rates are, you have to have enforcement mechanisms to make sure (corporations) pay them.”

“If the government closed that gap they stand to gain $10 billion every year. Think about what you could do with $10 billion each year. That’s a national child care program. That’s any government’s signature program. Even if you’re fiscally conservative, you could use it to reduce the deficit. That’s not an insignificant portion of revenue,” said Brennan.

WHAT WOULD $10.5 BILLION BUY?

Hire 30,678 new doctors (at average income of $339,000 per year)

1,768 new streetcars

Put the Gardiner Expressway underground

Build electric high speed (300km/hr) rail corridor Montreal--Ottawa--Toronto

Build 11,560 km of bike paths

Provide 1.2 million child care spaces

8 new heavy-duty icebreakers

Make college tuition free for 1,679,858 students

(On average, undergraduate students paid $6,191 in tuition fees in 2015/2016)

Hire 30,678 new doctors

(at average income of $339,000 per year)

1,768 new streetcars

Put the Gardiner Expressway underground

Build electric high speed (300km/hr) rail corridor Montreal--Ottawa--Toronto

Build 11,560 km of bike paths

Provide 1.2 million child care spaces

8 new heavy-duty icebreakers

Make college tuition free for 1,679,858 students

(On average, undergraduate students paid $6,191 in tuition fees in 2015/2016)

The last year that corporations paid as much income tax as people was 1952.

That year, the Canadian government was flush with money and used it to start setting up the social safety net with the establishment of the Old Age Security pension program. The private sector was also doing well, as corporate capital investments hit record levels and wages soared. The postwar boom was in full swing and the wealth was being enjoyed widely: Suburbs were exploding, schools and hospitals were built and new highways were laid down across the country.

This era of public and private prosperity” “unrivalled in our history” said then-federal finance minister D.C. Abbott came after Canada had twice imposed an “excessive profits” tax during both world wars.

Excessive profit, or rent, is an economic term used to describe profit beyond what is needed to keep a business running.

For the first half of the 20th Century, the Star campaigned for establishing and keeping this excessive profit tax in place, repeatedly arguing: “There is, in fact, no better or juster source of tax revenue than unreasonably high profits.”

Under publisher Joseph Atkinson, the Star’s editorial board made this argument for taxing corporate profits in 1946: “A special tax should be levied upon profits in excess of a reasonable amount ... The principle of imposing a proportionately higher tax upon high incomes of individuals is recognized as just, and should be in a measure applicable to the profits of corporations when these are beyond reason.”

Today, Canada’s economy is the strongest in the G7, but municipal, provincial and federal governments have to borrow money every year, or dip into savings, to make ends meet. Inequality is at an all-time high. The rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer and public infrastructure from transit to social housing is failing and falling apart.

Average weekly earnings for non-agricultural industries were $54.13 in 1952, a 9 per cent increase from the year before. Adjusted for inflation, that would be $502.53/week.

In 2016, the average weekly wage was $956.50, a 0.3 per cent increase over the year before.

Between 1949 and 1954, Canada’s first subway was built along Yonge St. in Toronto. The construction budget was $50.5 million, or $464.5 million in today’s dollars.

After years of slim budgets and inadequate maintenance, there was a mass breakdown of air conditioning on the subway during the summer of 2016. At its peak, a quarter of all subway cars on line 2 were “hot cars” with internal temperatures over 32 degrees. The city spent $13 million to replace the broken A/C units.

The Gardiner expressway was built between 1955 and 1966, at a cost of $103 million, or about $766 million in today’s dollars.

The raised highway has become so neglected that pieces of concrete have been falling from its underside, damaging cars for the last decade. It will cost $3.6 billion to rebuild the crumbling eastern end of the expressway.

The federal government introduced the Public Housing Program in 1949, which led to a 10 fold increase in social housing in the 1960s, when more than 20,000 units were built each year. One of the first major projects was Regent Park in Toronto, where more than 2,000 subsidized units were built between 1947 and 1960.

Currently, public housing in Toronto has a $2.6 billion repair backlog, and foresees closing more than 7,500 units over the next 5 years. Regent Park has been almost entirely torn down and replaced by a mixed development of subsidized and market units.

In 1952, there were 1,233 hospitals in Canada with 146,032 beds.

In 2015, there were 719 hospitals in Canada with 93,595 beds.

In 1955, there were 115,835 primary and secondary teachers in Canada and 3,295,000 students (28.4 students/teacher).

In 2015, there were 445,175 primary and secondary teachers in Canada and 5,055,987 students (11.3 students/teacher).

Average weekly earnings for non-agricultural industries were $54.13 in 1952, a 9 per cent increase from the year before. Adjusted for inflation, that would be $502.53/week.

In 2016, the average weekly wage was $956.50, a 0.3 per cent increase over the year before.

Between 1949 and 1954, Canada’s first subway was built along Yonge St. in Toronto. The construction budget was $50.5 million, or $464.5 million in today’s dollars.

After years of slim budgets and inadequate maintenance, there was a mass breakdown of air conditioning on the subway during the summer of 2016. At its peak, a quarter of all subway cars on line 2 were “hot cars” with internal temperatures over 32 degrees. The city spent $13 million to replace the broken A/C units.

The Gardiner expressway was built between 1955 and 1966, at a cost of $103 million, or about $766 million in today’s dollars.

The raised highway has become so neglected that pieces of concrete have been falling from its underside, damaging cars for the last decade. It will cost $3.6 billion to rebuild the crumbling eastern end of the expressway.

The federal government introduced the Public Housing Program in 1949, which led to a 10 fold increase in social housing in the 1960s, when more than 20,000 units were built each year. One of the first major projects was Regent Park in Toronto, where more than 2,000 subsidized units were built between 1947 and 1960.

Currently, public housing in Toronto has a $2.6 billion repair backlog, and foresees closing more than 7,500 units over the next 5 years. Regent Park has been almost entirely torn down and replaced by a mixed development of subsidized and market units.

In 1952, there were 1,233 hospitals in Canada with 146,032 beds.

In 2015, there were 719 hospitals in Canada with 93,595 beds.

In 1955, there were 115,835 primary and secondary teachers in Canada and 3,295,000 students (28.4 students/teacher).

In 2015, there were 445,175 primary and secondary teachers in Canada and 5,055,987 students (11.3 students/teacher).

Average weekly earnings for non-agricultural industries were $54.13 in 1952, a 9 per cent increase from the year before. Adjusted for inflation, that would be $502.53/week.

In 2016, the average weekly wage was $956.50, a 0.3 per cent increase over the year before.

While Canadian governments have trouble coming up with cash for public services, Canadian companies are rolling in dough.

Among Canadian corporations, one sector emerges as the most profitable. It’s also the sector with the companies that pay the lowest taxes: banks.

Last year, Canada’s Big Five banks BMO, CIBC, RBC, Scotiabank and TD occupied the top five slots on Report on Business Magazine’s Top 1000 ranking of the country’s most profitable companies. Collectively, they booked $44.1 billion in pre-tax profit. (Their just-reported 2017 profits were even higher.)

That same year, the Star/Corporate Knights analysis found those five banks avoided $5.5 billion in tax.

This was not a one-off. Over the past six years, while the Big Five have been posting record profits, the tax rate they paid has dropped.

According to Statistics Canada, pre-tax profits in the banking sector as a whole soared by 60 per cent from 2010-2015. During that period, the sector’s tax rate (taxes paid divided by pre-tax profit) has dropped by almost the same amount.

Banks reduce their taxes by far more than other corporations. In 2015, businesses in the rest of the economy (including the banks’ credit union cousins) paid taxes at a rate triple that of banks.

This number is skewed by the huge losses oil and gas firms suffered in 2015. If oil and gas companies are removed, the tax rate paid for non-financial companies is still 24 per cent in 2015, or 2.5 times greater than banks.

Not only do banks pay a lower tax rate than other companies, Canadian banks pay at a lower rate than banks in other countries.

While all banks legitimately reduce their tax burdens through depreciation, investment losses, loan interest writeoffs and tax credits, Canadian banks use these measures to erase more tax than their global competition. We did an international comparison and found Canada’s big banks have the lowest tax rate in the G7.

This November, when the Senate was discussing closing loopholes for small corporations, Senator Scott Tannas asked Finance Minister Bill Morneau, “why wouldn’t you hunt where the ducks are with the big banks?”

“If we could get them to pay what should be a fairly reasonable average between their U.S. operations and Canadian, we’d be billions ahead. I don’t understand why, year after year, only Bay Street has a special rate,” Tannas said.

How do the Canadian banks do it?

The Big Five earn the vast majority of their revenue in Canada and the U.S., which has a higher corporate tax rate than Canada. Yet in their financial statements to investors, the banks declare that lower tax rates in their “international operations” helped them reduce their taxes by $6.5 billion over the past six years.

While the banks don’t disclose how they lowered their tax bills through their international operations, they all have subsidiaries in tax havens.

Many of these tax haven subsidiaries have tiny offices, but account for massive profits. TD, for instance, has a subsidiary in Ireland that is valued at over $1 billion, even though TD Ireland employed only two of the bank’s more than 85,000 staff.

Canadian banks have subsidiaries in Barbados (0.25 - 2.5 per cent corporate income tax), the Cayman Islands (0 per cent), Ireland (12.5 per cent), Bahamas (0 per cent), Bermuda (0 per cent) and Luxembourg (starts at 19 per cent, but can be much lower as many multinational companies negotiate special tax deals).

All of these tax havens have something in common: they have a tax treaty or Tax Information Exchange Agreement (TIEA) with Canada. These treaties and agreements were meant to prevent the double taxation of corporate profits, but in practice they make it possible for companies to avoid paying tax altogether, recording profits where there are low or no income taxes and then repatriating this income to Canada tax-free.

Canada has admitted this is a problem, and this year joined 67 countries in an international effort to crack down on a widespread tax avoidance method called “profit shifting,” where a corporation performs internal transactions to concentrate its profits in tax havens.

“We want to make sure that large companies aren’t inappropriately having expenses in high-tax jurisdictions and taking profits in low-tax jurisdictions,” said Morneau in the Senate last month. “We want to have rules that appropriately force people to pay taxes in jurisdictions where the business activity is actually happening.”

NDP justice critic Murray Rankin suggests the government go one step further and explicitly ban corporate transactions without any “economic substance” a move, he says, that will hamper companies’ ability to exploit offshore tax loopholes.