Census 2016: Spike in number of Canadians cycling, taking public transit to work

TheGlobeAndMail.com

Nov. 29, 2017

Oliver Moore

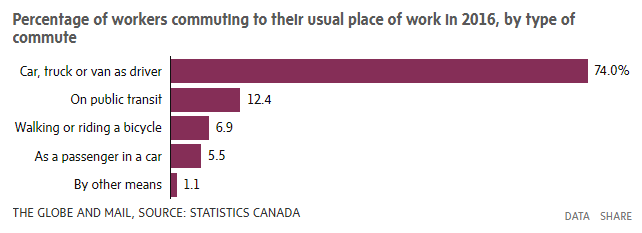

There have been big jumps over the last two decades in the number of Canadians cycling and taking transit to work, while the increase in car commuting, which remains the method used by most people, lagged behind the rate of population growth in major centres.

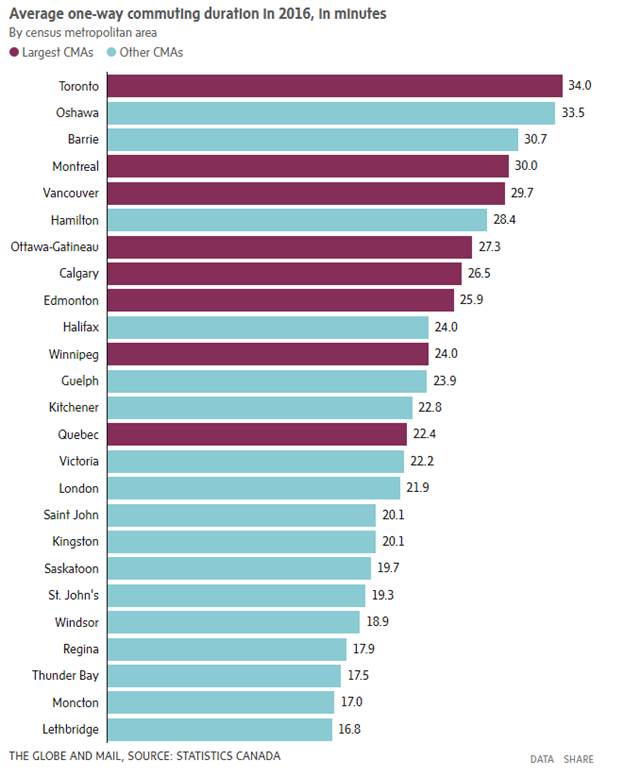

The new numbers are part of a release of census data that paints a picture of a country that is gradually changing how it gets around. The shift comes as average commute times in Canada's biggest cities get slightly longer, a by-product of worsening traffic that may be pushing people to adopt new ways to get to work.

"Driving can be excruciating in Toronto," said Jared Kolb, executive director of the advocacy group Cycle Toronto. "People that are accustomed to driving a car, having their space and moving in their own time, you get that on a bike."

The bulk of Canadians still drive to work, a method used by about 80 per cent of commuters nationwide. That figure drops to less than 70 per cent in the country's three biggest cities, where there are the best transit options and the biggest growth in cycling. This is the first time in 20 years that the proportion of driving commuters has been below 70 per cent in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.

According to Statistics Canada, the commuter population in census metropolitan areas, which are cities with populations of 100,000 or more, went up by 35.9 per cent over the last two decades. During that time, the number of people using bicycles as their main method of commuting nearly doubled, rising 87.9 per cent, and the number of people taking public transit rose 58.7 per cent. The number of people driving increased 31.5 per cent.

The Statistics Canada data show that "active transportation," which is defined as walking or cycling to work, was used last year by 6.7 per cent of Torontonians, 7.2 per cent of Montrealers and 9.1 per cent of Vancouverites. The largest percentage in the country was in Victoria, where 16.9 per cent used active transportation as their main way to commute.

The figures for other cities suggest weather does not play much of a role in whether people walk or cycle. Ottawa-Gatineau, where 8.7 per cent used active transportation, was only slightly lower than much-warmer Vancouver. And the cold cities of Winnipeg and Calgary, at 6.2 per cent, were not far behind Toronto.

Toronto had the country's highest share of transit users last year, with about one in four commuters riding its buses, streetcars or trains. Montreal was a bit lower and Vancouver, where one in five were on transit, had the fewest of the country's biggest cities. But Vancouver has seen the biggest increase in transit riders, nearly doubling their percentage in 15 years. Statistics Canada noted that the city has expanded its Skytrain rail network and its bus service, changes which the agency said "could explain part of the increase" in transit use.

Gordon Price, a retired director of The City Program at Simon Fraser University who was a Vancouver councillor for 16 years and sat on the board of Translink, the regional transit agency, said there's "no question" that transit investments were bearing fruit.

"The number of vehicles coming into the core is roughly where it was in the 1960s and 1970s," he said. "If you've built your city around the automobile, you will get drivers; if you build your city around transit, you will get riders."

Although travel times for car commuters remain a hot topic, garnering the attention of politicians in many cities, the census data remind that transit riders spend more time getting to work. In fact, the bulk of the overall increases in travel times can be attributed to the longer journeys by people on transit.

The Statistics Canada data show that times to get to work in most communities were roughly the same in 2016 as five years earlier. A minority were shorter, and most were marginally longer. Of the more than 150 municipalities analyzed, only four – Midland and Wasaga Beach, in Ontario, and the Atlantic communities of Bay Roberts, Nfld., and Campbellton, N.B. – had their one-way commutes extended by 2.5 minutes or more.

The community with the biggest decrease in average commute time was Wood Buffalo, Alta., which saw a 6.5-minute drop from 2011 to 2016. The same community also saw the biggest drop in its median commute distance, from 68.7 kilometres in 2011 to 8.6 kilometres last year.

The data also shows that the sort of ultralong-distance commutes that can dominate the political discourse are unknown to most people. Toronto's median one-way commute grew slightly, from 9.3 kilometres to 9.6 kilometres, over the last two decades. Over that same period, Montreal's median commute remained unchanged at 8.2 kilometres and Vancouver's shrank slightly, from 7.7 kilometres to 7.4 kilometres.