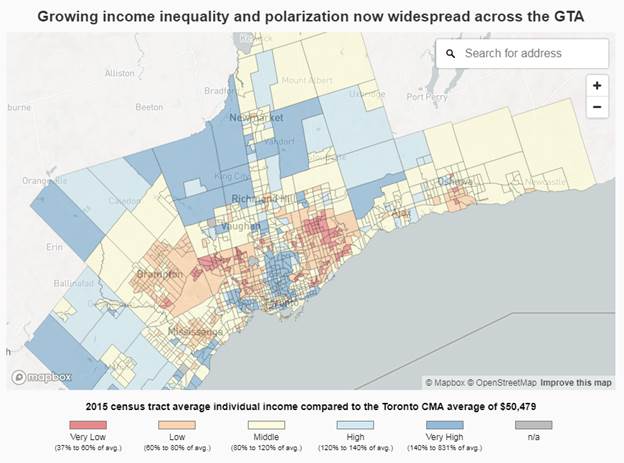

Toronto region becoming more divided along income lines

Across the GTA, the gap between rich and poor is widening, while middle-income areas are disappearing, United Way analysis of census data shows.

TheStar.com

Nov. 1, 2017

Laurie Monsebraaten

Toronto, long celebrated as a city of neighbourhoods, has become a collection of islands segregated by income, according to a new analysis of the latest census data.

Equally troubling is that this 40-year trend for Toronto has spread beyond the city’s boundaries into areas such as Peel where for the first time a majority of neighbourhoods are low-income, says a report by United Way Toronto and York Region being released Wednesday.

“The data shows that the challenge of growing income inequality and polarization is now widespread throughout the region,” says the study, an update of the agency’s 2015 Opportunity Equation report that dubbed Toronto the “inequality capital” of Canada.

“What’s sobering is that the majority of all the neighbourhoods in the GTA are segregated into either high- or low-income and the middle is vanishing. This is no longer just a Toronto or city issue,” said United Way President and CEO Daniele Zanotti.

“This report gives us pause on the region we are and the region we risk becoming if we don’t double down on good jobs, make sure our young people connect to the pipeline to those good jobs, and ensure that background and circumstance are not conditions for success,” he added.

According to the 2016 Census, the average individual income before taxes in the GTA in 2015 was $50,479. Using data released last week, the report maps individual incomes by “census tract,” or small, relatively stable areas with between 2,500 and 8,000 people, to tell the story.

“The gap between the rich and poor has continued to rise in major cities throughout the country,” says the report, which also mapped Census Metropolitan Areas (CMA) centred around Vancouver, Montreal and Calgary. But the Toronto CMA remains the inequality capital of Canada “and we’re at risk of getting stuck in this position,” the report warns.

Income inequality measures who gets how much of the pie, compared to other people or neighbourhoods while “polarization” looks at how incomes migrate to opposite ends of the spectrum as the middle disappears. Together, both phenomena prevent people from getting ahead and threaten Canadian values of fairness and opportunity, the report argues.

Ashleigh Kelk, 33, of Brampton, who dreams of getting a social work degree and a full-time job in the field, is an example of how residents in low-income areas are striving to improve their lives, but lack the opportunity to do so.

The single mother lives in one of Peel Region’s low-income neighbourhoods near Kennedy Rd. S., and Clarence St. and struggles to raise her two school-age children on a part-time job she loves at the Journey Neighbourhood Centre. But the job pays just $14 an hour, or less than $15,000 a year. And with social assistance, her total income before taxes amounts to about $25,000 a year making it “nearly impossible” to get ahead, she says.

“The cost of rent is excessive, food is excessive and you are penny pinching all the time just to make ends meet,” she said Tuesday. “At this point, I am just looking for second part-time job.”

Two decades ago, you could find the same grocery store chains in almost every neighbourhood, but today you get Pusateri’s enclaves and No Frills ‘hoods, said University of Toronto community planning professor David Hulchanski. His Neighbourhood Change Research Partnership worked with the United Way on the report.

In the 1980s, Toronto was dominated by middle-income neighbourhoods, said Hulchanski, who has tracked Toronto’s “three cities” of high-, middle- and low-income areas since 1970.

But now, those neighbourhoods make up just 29 per cent of the city, while almost half of Toronto census tracts (48 per cent) are low-income where residents bring in between 60 per cent and 37 per cent of the average GTA income.

In Toronto’s wealthiest areas, incomes have more than doubled since 1980 from $163,000 to $420,000 in today’s dollars, according to the United Way.

Meanwhile, in the regions outside Toronto, there are 15 per cent more low-income neighbourhoods since 2000. And the trend is most pronounced in Peel where the percentage of low-income neighbourhoods has doubled from 24 per cent to 52 per cent since then.

Lynn Petrushchak, executive director at the Dixie Bloor Neighbourhood Centre in Mississauga, sees the impact daily at her agency that serves an area of growing poverty sandwiched between high-income areas to the north and south.

“Our neighbourhood is an island of need in a sea of affluence,” she said in an interview. “Residents are living in tenuous situations that make moving forward very difficult.”

People in affluent neighbourhoods have networks, technology, peers and colleagues they can use in a time of need, Petrushchak said.

“But people in our area don’t have those networks. Their next-door neighbour doesn’t know how to help them. Their brother doesn’t know either because he’s in the same sort of situation,” she said.

“Even though there are good services, they may not know about them. They may not have the confidence to use them. The services may not be open when they are available. And they don’t know what to do with their kids while they are seeking help,” she added. “It’s not an easy time for these people, for sure.”

According to this latest report, only Durham Region in the GTA has bucked the inequality trend with almost three-quarters of its neighbourhoods still made up of middle-income residents.

Law clerk Julia Verconich, 37, is one of them. The former Toronto Beach resident works at a downtown firm and earns near the GTA average income. But when it came time to buy a house, sticker shock drove Verconich and her fiancé Chris Harvey, 34, a tradesman, to Courtice, northeast of Oshawa.

“We loved living just steps from the water in the Beach,” she said of the apartment the couple rented south of Queen St. E. “But there was just nothing we could even remotely afford in Toronto.”

And she is not alone. “Our neighbourhood is full of people like me who have come from Toronto.”

But there are trade-offs. Although the couple has a $400,000 house they can afford, it means a commute of more than an hour to work both ways by GO Transit for Verconich and daycare drop-offs at 7 a.m. for their 15-month-old daughter Jade. Since she can’t make it home in time before the daycare closes at 5 p.m., Verconich relies on her parents for pick-up, a luxury she knows many in the area don’t share.

High levels of income inequality are linked to many social and economic problems including lower levels of trust, decreased concern between people from different backgrounds, higher rates of violence and mental illness and unstable economies, the report notes.

Since its last report, United Way Toronto has merged with York and most recently Peel.

“While the issues are the same — demographic shifts, labour trends — the solutions in Mississauga are going to be very different than what we might roll out in Markham or in Malvern,” Zanotti said.

In 2016, more than 200 United Way services helped over 2 million individuals and families across Toronto and York Region. The charity’s 2016-17 budget is $111.2 million and its fundraising goal is $103 million.