Toronto residents do not make enough money to thrive, report says

Report finds that residents need more than double what they earn on minimum wage, and that social policies need to be adjusted to meet the needs to present-day society

TheStar.com

Oct. 3, 2017

Fatima Syed

Mary Hynes, 74, is a retired teacher with a stable pension plan that is adjusted to the cost of living. Still, not long ago, she had to decide whether to get new tires for her car or have her teeth fixed.

Alex Lach, 31, just started a new job in sales, and is already concerned about whether or not he’s going to be able to meet his economic and social goals in life.

Both Hynes and Lach were part of a focus group earlier this year to inform a research study looking into what it really costs to “thrive” in Toronto.

The research study was spearheaded by Nishi Kumar, 25, a junior fellow at the Wellesley Institute. Informed by her masters in Public Health from the University of Toronto, Kumar set out to reframe the standards of social policy, which are mainly geared toward basic survival.

“Thriving,” according to Kumar, is more than the bare minimum, more than just food and shelter. It demands, what she calls, a “higher standard of living that promotes good health today and in the future.”

“It’s time to start looking beyond minimum wage and minimum survival,” agrees Hynes, “How can we have a better life as opposed to an adequate life? If all you’ve got is enough to survive, you can’t really participate in the community…You’re in effect isolated.”

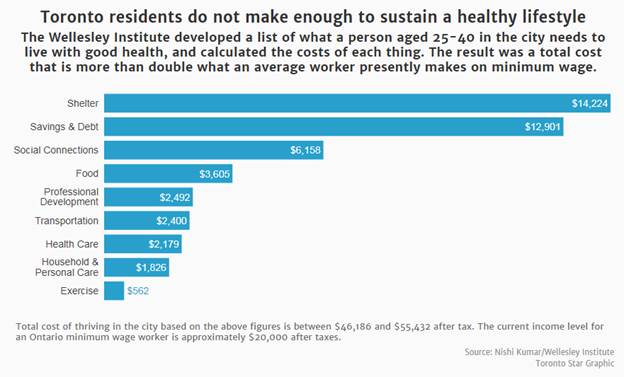

In her report, “Thriving in the City: What does it cost to live a healthy life?” which the Star had exclusive access too, Kumar found that the cost of thriving in the Greater Toronto Area for a single person aged 25-40 is between $46,186 and $55,432 after tax. This is more than double the current income level for an Ontario minimum wage worker, ($20,000 after taxes).

A future minimum wage worker earning $15 per hour would also fall well short of this figure, with an after-tax income of approximately $25,500, barely half of what it would actually cost to thrive.

“In the current conditions, with the current social safety net, and the current minimum wage, there’s no way you could live a healthy life in Toronto,” said Kumar.

The reason for this high total cost of thriving, according to the report, is a fuller list of bare essentials that promote not just survival items like food and shelter, but things that contribute to long-term positive mental and physical health. These include:

- Transportation costs, including public transit, car payments, etc.

- Additional (uninsured) health care such as dental and glasses.

- Personal care costs, such as laundry, haircuts and clothing.

- Social costs, such as cellphone plans, Wi-Fi, travel, subscriptions, money for entertainment (cinema tickets, restaurant meals, etc.), and donations.

- Professional development costs such as continuing education, software subscriptions, networking conferences, and technological purchases/maintenance.

- Savings for retirement, and debts (OSAP, credit card, etc.)

“Some of those things that I think in some policy rhetoric we talk about as being add-ons but in reality they’re not,” said Kumar. “What of those things can a person in today’s society give up?”

Part of the problem, she said, is that social policy has not kept up with the changing demographics and lifestyles of Toronto’s population. The latest census results show that Canadians aged 20 to 34 living with their parents has increased to 34.7 per cent, up from 33.3 per cent five years earlier.

The share of young adults living at home was highest in Ontario, at 42.1 per cent; and, in Toronto, almost one in every two young adults live with their mom or dad.

The census also found that, of 14 million households, 65.2 per cent made a contribution to some kind of retirement fund in 2015 — the most recent year for which data was available.

“I think folks are getting squeezed from all sides and the question that arises is does it have to be that way,” said Kumar, “Is there an alternative paradigm that we can start to think about?”

Shifting demographics have changed what Toronto residents consider a need. Kumar found that people didn’t need things like cable TV anymore. But visiting family has become increasingly important for a growing diverse population, as has education and professional development.

“People are thinking about future needs more so today,” said Kumar. “They’re thinking about what ifs.”

For older folks, Kumar found that the concern to save for home care was important, as was travelling to see their grandkids and family in other cities.

“If you have fun, it seems like you’re stealing from yourself,” said Hynes. “If you go for a movie, you think maybe you shouldn’t have breakfast.”

The total cost Kumar has calculated isn’t an ideal income, but illustrates “the total resources required to live a healthy life in the GTA,” according to the report. This baseline figure could be met by rising income, but also by improving public services, social programs, employer-sponsored benefits, and community facilities.

The report offers some suggestions to close the gap between what GTA residents are earning and what they need to live fully. Initiatives to increase provincial investment towards post-secondary tuition grants to reduce debt burdens, or increasing federal investment in affordable housing that would reduce shelter costs could help.

“Both employers and public services need to step it up and need to think about what people need to have good health over time,” said Kumar. “It used to be that the employer absorbed all these costs, now it’s just on you.”

While both Hynes and Kumar view the new minimum wage as a step in the right direction, it’s not enough. “With the way its set up now, everything is temporary, and you’re responsible for everything” said Hynes.

“But to be a full member of society, you need more than the minimum.”