Canada lags in conservation efforts

Annual study looking at the UN Convention on Biodiversity obligations shows country has done far less than other nations in preserving areas from development, leaving it in last place among G7 members

TheGlobeAndMail.com

July 23, 2017

Gloria Galloway

Canada is behind the world’s other economic leaders when it comes to protecting its lands and fresh waters and is well off pace of meeting the international commitment it made seven years ago to nearly double the size of its protected regions by 2020, according to a new national study.

The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society’s (CPAWS) annual report takes a hard look at how far Canada has gone toward complying with its obligations under the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity, which was signed by the previous Conservative government and aims to halt widespread biodiversity loss. The results suggest this country is an environmental laggard.

Canada has 20 per cent of the Earth’s forests and 24 per cent of its wetlands, but has done far less than many other countries when it comes to putting areas beyond the reach of development, according to the study to be released Monday.

Protection of lands and waters is critical for our survival, said Éric Hébert-Daly, CPAWS’s national executive director.

“We’re a part of nature and, if nature is not protected around us, things like clean water and clean air and things we rely on for the survival of the human species, as well as every other species on Earth, is undermined,” Mr. Hébert-Daly said. “So protected areas are the linchpin in our survival and the survival of the planet.”

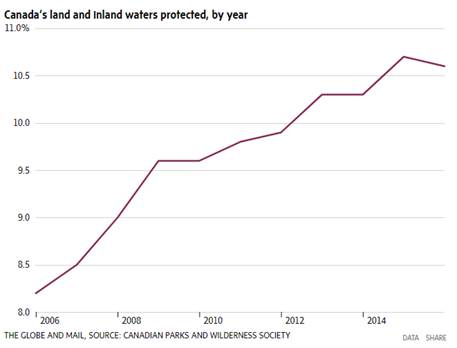

In 2010, when 9.6 per cent of its lands and fresh waters were protected, Canada agreed to meet the international target of protecting 17 per cent of its territory within a decade.

But, with just three years left to go before that deadline, the amount of land and water protected has climbed by just one percentage point, to 10.6 per cent, the report says.

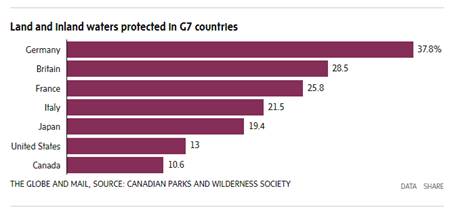

That puts Canada behind all of the other G7 countries, including the United States. Germany, which is the leader among that group, has protected 37.8 per cent of its lands and waters.

It also leaves us lagging behind a number of other countries with large masses, including Brazil and China.

“There are a number of countries that we highlight in our report that are actually well beyond the 17 per cent and frankly driving to what nature actually needs, which is closer to 50 per cent,” Mr. Hébert-Daly said. “We are well below average, if you want to look at it from that perspective.”

Part of the problem, he said, is that Canadians falsely assume there is no development taking place on the 90 per cent of Canada that is publicly owned. The other problem, Mr. Hébert-Daly said, has been a lack of political will.

“I think there has been no concerted focus on this issue,” he said. “The jurisdictional issues can sometimes get in the way in terms of people thinking, ‘Well, that’s a provincial responsibility,’ because provinces are responsible for land use.”

But this year, that changed. For the first time since 2010, environment ministers from the provinces and territories sat down with federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna to discuss the 2020 goal and how to reach it. That marked the start of an effort to move from a collection of protected areas to a connected network, said Marie-Pascale Des Rosiers, a spokeswoman for Ms. McKenna.

“A connected network will play an important role in contributing to the recovery of species at risk,” said Ms. Des Rosiers, “and in mitigating the impacts of climate change by maintaining resilient ecosystems and by helping plants, animals and their habitats adapt to changes.”

A national advisory panel has been created to provide governments with advice, based on science and traditional knowledge, on how Canada can achieve its target and must report back later this year. In addition, an Indigenous Circle of Experts has been set up to provide expert advice on biodiversity conservation.

“There is a tremendous amount of collaboration and work going on right now that even a year ago we did not see any hint of. So that’s at least a step in the right direction,” Mr. Hébert-Daly said.

The CPAWS report highlights a number of sites in the country that could easily be set aside from development within the next three years to allow Canada to reach its commitment.

“Absolutely, it is possible for us to get to that target by 2020,” Mr. Hébert-Daly said. “But, more importantly, we have to be careful not to let 17 per cent become our ceiling. We have to be thinking about 17 per cent as a milestone on our journey to what nature actually needs in terms of its security and its ability to survive over the long term, and scientists are saying that’s much closer to 50 per cent.”