How a 73-year-old is hoping to link the GTA through water-based transportation

TheGlobeAndMail.com

July 21, 2017

Oliver Moore

It's a solution as obvious as it is elusive: Toronto sits on the shore of a Great Lake, and its roads are often jammed, so why not commute by water?

It's an idea that dates back decades and one that comes with the progressive cachet of having been supported by urbanist legend Jane Jacobs. But businesses trying to tap this market have consistently failed. Water-borne commuting – with the notable exception of Toronto Island dwellers who take a ferry to the mainland – is more complicated than it seems. For now, it essentially doesn't exist in Toronto.

One man is trying to change that. To do it, he needs a couple of boats and to get them, he needs $10-million.

A 73-year-old with a background in mining exploration, Bruno Caciagli may not seem an obvious person to float such an idea. But the amateur sailor and resident of Beamsville, between Hamilton and St. Catharines, says that it came to him after a conversation with a local politician on how to improve the area.

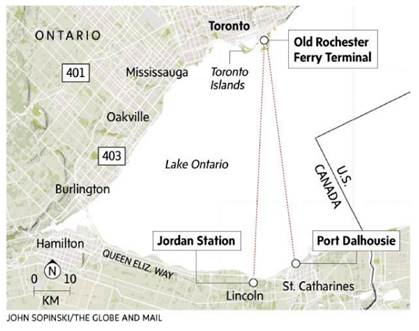

He wants to operate from Port Dalhousie and Jordan Station, serving each of these Niagara Peninsula destinations with a single boat doing seven direct trips a day across Lake Ontario to Toronto, for a total of 14 round trips daily. He hopes to capture slices of both the commuter and tourist markets, carrying what he says is a conservative starting estimate of 980 people a day.

The business plan calls for a one-way fare of $25, plus tax, and he says it won't require a government subsidy to operate.

"If you live in this area, there is a need," Mr. Caciagli said in a phone interview. "Everybody who has had to go up and down the [Queen Elizabeth Way] recognizes there's a need. And, boy, if there's a need, there's a way."

At this point, the way forward includes finding a place to dock at the Toronto end of the journey. He also needs regulatory approval and a way to convey passengers to their final destinations once they're ashore. And he needs the money to fund a pair of as-yet-unbuilt hovercraft. He figures some of this capital cost would come from government and some from private investors.

Toronto transit expert and blogger Steve Munro laughed aloud when he heard that the venture needs public funds to launch. He pointed to the city's Union Pearson Express, the airport rail link that promised to break even but needed a subsidy last year of about $16 a passenger. And he warned that politicians who are seduced by shiny promises that carry few people risk taking their eye off more important priorities.

"Why can't we just fling them across the lake?" he proposed facetiously. "We can set up a supertrebuchet in Jordan Station and fire people across the lake."

Although other cities have made water transportation work, in specific and limited ways, Toronto has not.

When campaigning for office in 2014, Toronto Mayor John Tory made a vague promise to explore the potential of water-borne commuting. A spokesman said that, since being elected, Mr. Tory has focused on "improving traffic and expanding transit options on land." A decade ago, Toronto Transit Commission staff were asked by their political masters to explore water-transportation routes into the core from Etobicoke and Scarborough. Their analysis effectively deep-sixed the idea, pointing to limited demand and the need for continuing subsidies as high as $39 a passenger.

Mr. Caciagli's proposal faces its own challenges.

In a letter, Ports Toronto seemed to pour cold water on the idea, telling Mr. Caciagli that it doesn't see the venture as a good fit for "an industrial cargo port" and unsuitable because of the noise it could generate and its impact on residents.

"As such, we would not be able to accommodate a hovercraft service on any of our properties," wrote Michael Riehl, the manager of marine operations at Ports Toronto, a federal agency. He did not respond to a call seeking further detail.

To a transportation journalist, the hurdles would seem to loom large. But Mr. Caciagli bats aside skeptical questions with the sort of irrepressible optimism required to make a living in mining exploration.

He said noise would be minimal, because the boats would come into the harbour slowly. And he argues that it's absurd to suggest it's somehow improper for his boats to use the same Toronto terminal that once hosted the defunct ferry from Rochester, N.Y. If that location doesn't pan out, he says he'll find another spot in the downtown core.

As for ground transportation, he knows it is key and says he'd work with transit on that, at the same time dropping a hint that there could be news in the coming weeks about a private role in this.

Mr. Caciagli points to the pollution-reducing effects of taking what he projects would be 600-900 cars a day off the QEW. That's a small fraction of the total on the highway, he admitted, but you have to start somewhere.

The concept has statements of support from the city of St. Catharines (which includes Port Dalhousie) and the town of Lincoln (which includes Jordan Station). And Mr. Caciagli said he is hearing positive noises from higher levels of government. But the idea will founder unless he can secure a place to dock in downtown Toronto.

"There's no way I can get [funding] lined up for sure before the route is agreed on," he acknowledged.