Guelph’s post-Mercury blues: How an Ontario city is coping without its local newspaper

A year and a half after its daily paper stopped printing, Guelph has become a living laboratory for the loss of traditional local media – a rising risk in communities across Canada. Simon Houpt explores what Guelphites have lost, and who’s trying to fill the void

TheGlobeAndMail.com

July 24, 2017

Simon Houpt

It must have seemed auspicious rather than ironic, back in July of 1867, in a town full of promise and a country not yet two weeks old, to name a newspaper after the Roman god of financial gain. And so Mercury (who was also, of course, the god of communication) became the namesake of the new daily newspaper of Guelph, Ont.

The publication lived an important and, sure enough, financially gainful existence for most of its life, until a more contemporary god – a monstrous hydra with ever-more-sprouting heads named Craigslist and Google and Facebook and whatever the Latin word is for Internet – decreed that information wanted to be free. Or, at least, that people thought it should be, so they largely stopped paying for it.

Which left the Guelph Mercury in retrograde. And on Jan. 29, 2016, its parents at Metroland Media Group Ltd., a division of Torstar Corporation, euthanized the paper about five months shy of its 149th birthday.

If that was likely the first time most Canadians ever thought of the Mercury (or the 141-year-old Nanaimo Daily News, shuttered the same day, by Victoria-based Black Press), it certainly was the last. Amid the tweeted farewells, loyal readers and local politicians turned out for speeches on the front stoop of the newspaper’s office, as fat snowflakes fell from the sky and mingled with their tears. And then the 26 newly unemployed staff, including eight in editorial, turned out the lights in the newsroom on Macdonell Street one last time, and the rest of the country flicked to the next story in their social-media feeds.

But that’s precisely when one of the most important stories in Guelph’s recent history began, the tale of what happens when a large and growing city is left without the connective tissue of a daily newspaper. And the story is much larger than Guelph: The city of 132,000, about an hour’s drive west of Toronto, has now become something of a living laboratory for dozens of other places across the country – large metropolises and small bedroom communities alike – which may be in danger of a similar fate if Canada’s two largest newspaper chains can’t find a way out of a devastating economic malaise.

The Mercury’s death was not the end of local news in Guelph. Over the past 18 months, outlets sniffing opportunity have opened new operations or expanded coverage: Metroland’s own Tribune, a twice-weekly tabloid published since 1986 and distributed free to most homes in the city, has bulked up its reporting ranks. (It also rechristened itself the Mercury Tribune and took possession of the Mercury’s website.) But in conversations with dozens of Guelphites over the past month, The Globe and Mail has found high anxiety at the overall drop in news, despair over a growing sense that city politics are becoming nastier and more polarized without the moderating influence of a daily, and a creeping dread that fact-free U.S.-style politics – enhanced by the canny use of social media by those in power – could be spreading north.

“I honestly believe we have an emergency in this city,” says Tony Leighton, a local freelance writer.

As media dies, not everyone cares

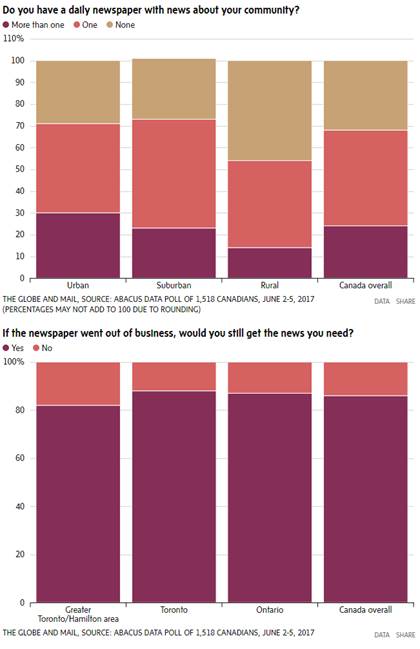

Before we continue, an acknowledgment: Odds are you don’t think this is a big deal. In a survey conducted last month by Abacus Data Inc., 32 per cent of respondents said they already live in communities with no daily newspaper, 44 per cent have one daily and 24 per cent have more than one. But a whopping 86 per cent of respondents across the country said that if their local daily (or dailies) went out of business, they would still be able to get the news they feel they need.

We are, after all, drowning in news, a sea of information just a click or two away. And even as the industry cries poor, events over the past year have financially rejuvenated a handful of outlets, especially in the United States. The New York Times and The Washington Post, especially, have benefited from a so-called Trump Bump as readers, prompted by a chaotic presidency and concern over the explosion of fake news, rushed to buy new subscriptions to publications that proved their worth during the election campaign.

But most of the gains are going to a select few brands able to aggregate large audiences around stories of global importance (or at least bigly drama). Local outlets simply don’t have the same economies of scale. And newsrooms continue to hemorrhage: According to research released last month by the Washington-based Pew Research Center, total ad revenue for the U.S. newspaper industry (including digital) dropped more than 63 per cent in 10 years, from $49-billion (U.S.) in 2006 to an estimated $18-billion last year.

In Canada, there appears to be no end in sight for the financial losses at Postmedia Network Inc. The country’s largest chain by circulation, it publishes the National Post as well as 44 local dailies in 38 cities and towns, including all the paid daily newspapers in the 10 largest English-language markets besides Toronto and Winnipeg. It also publishes dozens of free community newspapers – many of which are the main source of local news – and their related websites.

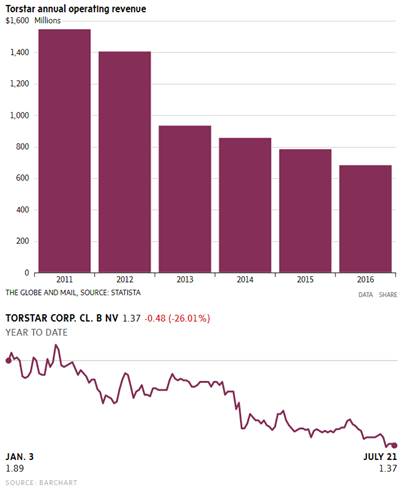

Meanwhile, operating revenue at Torstar Corporation, the country’s second-largest chain by circulation, which publishes the Toronto Star, the Hamilton Spectator and the Waterloo Region Record as well as more than 100 community papers, dropped more than 55 per cent from 2011 to 2016. Shareholder equity fell from $706-million to $326-million in the same period. This week, the stock price hit a historic low.

In the 2015 book Local Journalism: The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media, Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, the director of research at the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, argued that local dailies serve the vital if little understood role of “keystone media.” Even in straitened circumstances, that is, they operate the largest newsrooms in their local markets, digging for and grinding out original stories that are then picked up by radio and TV stations and other media. Chris Clark, who retired as editor of the Guelph Tribune two years ago, said that he used to wake up to the local oldies radio station CJOY. “The only reason I listened to it was for the news,” he says with a chuckle, “because I wanted to know what was in the Mercury that day.”

Local media hold governments and leaders accountable, provide a forum for people to learn about and chew over issues and help them stay plugged in to the life of their communities.

They also serve as an early-warning system, unearthing problems brewing under the surface that might later sweep across the country. When Donald Trump squeaked out his win last November, U.S. media were ridiculed for having failed to grasp the disenchantment among certain voting blocs, especially in the Midwest. But with local media lacking resources to dig deeply into stories, national outlets may have been slower to pick up on the social and economic convulsions in the heartland. All politics may be local, but if the only place for local voices to be heard is at the ballot box, politicians – and national media – are going to find themselves surprised a lot more often.

News over the breakfast table

If you drop in on the old Mercury newsroom on Macdonell Street nowadays, you’ll find a cheery staff manning something called the Guelph-Wellington Business Enterprise Centre, a government-sponsored knowledge hub where you can get help writing a business plan that is presumably more promising than the Merc’s. From there, you might saunter down the street to Breezy Corners Family Restaurant, a friendly diner with gingham curtains and orange accented walls, where a couple of dozen concerned residents gather over bacon and eggs every Thursday morning to hash out issues dogging the city. The coffee klatches – dubbed “Breezy Brothers Breakfasts” – are the brainchild of city councillors Phil Allt and James Gordon, who, after the Mercury’s closure, sought to replicate the vigorous debates from its letters-to-the-editor pages.

The other week, it being the start of summer, the agenda was a little loose: grousing about Canada geese and their propensity for pooping downtown (a never-ending issue to which the Mercury Tribune recently gave page-one treatment), affordable housing and development, Guelphites’ alleged resistance to properly sorting their garbage and complaints over parking. (plans for a large downtown parkade, which has been years in development, continue to lurch and morph).

And then, because a reporter from the big city had popped by, talk turned to the state of Guelph’s media. Someone pointed out that Rogers TV had recently closed its local studio (although it is still producing shows about Guelph from Kitchener, 30 minutes down the road). One fellow said he had felt “well served” by local media until the Tribune’s long-time city-hall reporter, Doug Hallett, retired recently. Mr. Hallett’s replacement had gone to high school in Fergus, just up the road, but he’d been away for years, working in Yellowknife and Oshawa, Ont., and the consensus among the Breezy breakfasters was that it would take him some time to get up to speed on local issues and personalities.

At the far end of the table, one woman stood up uncertainly. “The deaths are coming to me far too late,” she announced, briefly leaving her tablemates flummoxed. “I know there was a fantastic funeral on Monday, and I missed it. I wanted to be there, but I didn’t know about it, because the Tribune comes out on Tuesday.”

Mr. Allt, the councillor, clocked what she was saying, and nodded. “That’s interesting, because that mundane issue is not one that I ever thought of. The truth is, I’m relying more on social media for [obituaries].” A few people nodded.

Mike Salisbury, another councillor, acknowledged that social media has become an indispensable source of news, but he believes it has also sickened the city’s politics. “It’s become very abrasive and confrontational,” he said. “If something doesn’t go someone’s way, they say really mean, nasty, poisonous things on social media, and you just go, ‘Really? Does it have to be like that?’ It’s a very toxic environment.”

The Mercury used to have a moderating effect, he said: “If you said something really significant online, the press would have picked it up and checked it out.”

As breakfast wound down, a few folks grumbled about the social-media savvy of the city’s mayor, Cam Guthrie, who maintains a playful Instagram account, an upbeat blog and a busy Twitter feed with more than 11,000 followers. “He’s fantastic at it,” Mr. Salisbury offered. “He’s also going to be a major benefactor from this environment.”

What’s missing when news goes online

A couple of weeks earlier, Mr. Guthrie’s predecessor, Karen Farbridge, explained over the phone that – perhaps counterintuitively – she valued aggressive media coverage of city hall, especially if it peered into dark corners she could not reach. “You might think you have the capacity, as an elected official, to have information about everything, or that you’re aligned or in agreement with everything the administration does. That’s not how it works. The fact that a reporter might report on something that caused me or another elected official [to have] challenges, or the administration challenges – that’s part of it.”

Over the course of her time in office, which stretched from 2000 to 2014 (with one three-year interruption, during which Kate Quarrie served as mayor), Ms. Farbridge says the number of local reporters assigned to beats covering large institutions such as the school board and the courts shrivelled up. “So, press releases from those organizations drove the coverage, as opposed to having reporters embedded.” (“The joke,” says Mr. Clark, the former Tribune editor, “is that, when the police department’s PR officer is away, there’s no crime in Guelph.”)

“In more recent years as mayor, sometimes I would be the only person interviewed on a story, because there was simply no time [for the reporter to speak to other sources],” Ms. Farbridge says. “While you might think it’s great to be the only one, it’s not. You didn’t get the investigative reporting, which – to me, that’s part of a really healthy democracy.”

Even non-investigative stories can take a while to appear. Reporter May Warren, who won three Ontario Newspaper Awards during the 10 months she worked at the Mercury between late 2014 to summer, 2015, recalled spending a long day in court waiting for a specific case to be administered. While there, she observed a judge hand down sentences in two other cases – one of sexual assault, another of drunk driving – that didn’t include jail time, since the guilty men required medical attention and the judge was concerned they would be sent to solitary confinement because the prison infirmary wasn’t open.

“If I hadn’t have been there that day, that never would have gotten out,” she notes. “That’s the kind of thing people just don’t know about now, because there’s not enough resources.”

Filling the Mercury’s shoes

No one hangs around the courts any more, it’s true, but the stories didn’t stop after the Mercury shut down. Less than two weeks after Metroland pulled the plug, Village Media, a network of online community-news operations based in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., launched GuelphToday.com with two of the Mercury’s former reporters. The newsroom, a three-minute walk from their old office, consists of a jumble of desks in a disused jewellery store on Wyndham Street.

In addition to national and international wire stories, GuelphToday.com serves up about half a dozen quick, local news hits a day about events in town, city-council decisions and crime stories, along with a handful of regular freelance columns. It also publishes news releases from the Ontario Provincial Police and the City of Guelph, which are given the same editorial treatment as regular stories – grabby headline and informative subhead – and frequently played at the top of the site.

“We’re essentially trying to be the source for someone who wants to know what’s going on today,” explains Mike Purvis, Village Media’s managing editor, who oversees a stable of similar sites in Sault Ste. Marie, North Bay, Barrie and Timmins.

“I think we’re also trying to be that place where they’re having those conversations around what’s important to Guelph. It’s a cool city, a lot of history there, it’s a university town, full of academics and people who are not afraid to push boundaries and talk about what’s going on. It’s also a place that’s really growing, so there are those pressures, development’s always happening, not everybody’s happy with that all the time. Those people need a place to talk about those issues, those conflicts.”

Traffic at GuelphToday.com is increasing at a steady clip, according to Mr. Purvis, with 1.2-million page views in May, up 25 per cent since January. The site currently counts about 12,000 weekly unique desktop users, 25,000 mobile users (it’s best experienced on your phone) and about 6,000 tablet users.

In an e-mail conversation, Village Media’s chief executive Jeff Elgie said that annual costs for Guelph Today run about $300,000, and it is currently taking in a little more than $200,000 a year in advertising. He added that the company’s Soo and North Bay sites are profitable, and he expected Guelph’s to be as well: Each of the three cities has a strong sense of community, and few other media outlets chasing local dollars and audiences. (He says Barrie has not been profitable, which he chalks up to stiff competition from other media outlets and the fact that the city, about an hour’s drive north of Toronto, “acts more like a commuter community/part of the GTA.”)

Village Media wasn’t the only company that saw promise in Guelph. Metroland Media’s Tribune (or, rather, the newly renamed Mercury Tribune) also picked up another former Merc staffer, increasing its reporting ranks from two to three. (It also has a sports editor who writes regularly.) The paper was “inundated with requests for coverage,” editor-in-chief Doug Coxson says over the phone. “The community was expecting us to pick up where the Mercury left off.” Mr. Coxson says the paper is trying to do more investigative work. Still, community-news staples dominate: council decisions, announcements about new developments, crime briefs, feel-good stories about local heroes.

Another of the outlets that benefited from the Mercury’s disappearance is Guelph Speaks, a tart politics blog. Edited by a former newspaperman by the name of Gerry Barker, the blog seems to be the only outlet that regularly shows interest in digging deeply into the numbers on a handful of money-losing ventures overseen by the city. But Mr. Barker is also written off by many as an irritant, because he has a habit of slinging accusations of corruption at politicians and other media, sometimes without fully providing sufficient evidence. Last fall, a city executive filed a $500,000 defamation lawsuit against Mr. Barker. (Mr. Barker has filed a statement of defence and, in an e-mail to The Globe, denied he had defamed the executive.)

Mr. Barker has a mild-mannered counterpart in Adam Donaldson, an earnest fellow who aspires to provide Guelph’s most comprehensive coverage of local politics. After the Mercury closed, he revived a dormant blog of his, Guelph Politico, where he offers impressively detailed explanations of council meetings (which he also live-tweets) as well as podcasts of Open Sources Guelph, a weekly politics show he co-hosts on CFRU, the University of Guelph’s radio station.

Mr. Donaldson launched a campaign through the crowdfunding site Patreon to support his work full-time. It may be a quixotic quest: His evenhanded coverage seems unlikely to incite anger and therefore sharing on social media, which would help bring in sponsors. As of this week, he was only $185 toward his $1,000 monthly goal.

Still, Mr. Donaldson and Mr. Barker play by established rules. Some other communities struggling with thin coverage have had to grapple with outlets run by anonymous operators who have unknown agendas. During a conference last month on the state of local news, sponsored by the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre (RJRC) in Toronto, Brian Lambie, the president of PR firm Redbrick Communications, noted that, after Sun Media closed the Georgian Bay-area Midland Free Press in June, 2013, a number of new sites cropped up offering local coverage to the community of 16,000. But it can be surprisingly difficult to determine who operates them: Mr. Lambie told the conference there are suspicions that one blog is being run out of the local police station.

Signs of progress

Rob O’Flanagan is a case study of the changes roiling both the news industry in general and Guelph in particular. At 57, he has 23 years in the business, including a long stint at the Sudbury Star and nine years at the Mercury. With a laptop, digital camera, iPhone and voice recorder, he can crank out stories from anywhere. (And often does: Sometimes, it’s just too hot to work in the office, so he escapes to a café.) If the technological adjustments have come easily, the psychological ones are tougher.

“When you work for a daily newspaper in a community, that’s a prestigious thing to do, because there is that deep-rooted history,” he notes, sitting in the spartan GuelphToday.com office. (His fellow reporter, Tony Saxon, was on vacation.) “You feel that inherently. But when the Mercury closed, that evaporated. Now, it’s basically a startup, online daily news service that is new, that people aren’t familiar with. And you feel like a kid in a lot of ways, just starting out. And people have been just a touch more reticent to open up and to take it seriously.”

Still, he adds, “Over the past year or so that we’ve worked on this, people have warmed up to us. There’s a lot more name recognition. People for the most part seem to appreciate what we do, and that has won their trust.”

Mr. O’Flanagan says he’s usually working by 7 a.m., scanning social media and e-mail to see what might be worth covering. He’s obligated to crank out two to three stories a day. “The problem is, I’m used to being a daily news reporter, so I’m used to having more than two sources, and I’m used to writing kind of long. And I still want to do that. I don’t want to bang off three paragraphs and a photo. So I put a lot of pressure on myself.”

Are there stories he’d like to do, but simply can’t find the time?

“Oh yeah, absolutely,” he says quietly. “We have a big drug problem in the city. Particularly in the downtown. It’s really grown. Fentanyl, all the opiates, crack is still a big problem. It really seems to have changed the downtown culture in recent years. There are a lot more people panhandling in the streets. In this location, we hear a lot of street confrontations happening right outside the door.

“All of that would make just an exceptional story. But it would take two or three days to find people to talk to, to get the cops involved, the social agencies that deal with these kinds of things.”

Is he really saying that he’s so busy feeding the beast that he literally can’t report on something happening right outside his door? “Yeah, that’s a good way to characterize it,” he says softly, then pauses. “I feel I would not be able to produce the content that I need to produce on a daily basis if I focused on that kind of story.” He looks up. “It’s actually very discouraging.”

Mr. O’Flanagan isn’t the only one seeing stories that won’t get written. Phil Andrews, the Mercury’s last managing editor, left journalism after the paper closed and now works as a spokesman for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. “I think our local media are doing a good job of saying, ‘What’s that smoke in the sky and where’s it coming from?’ Where we’re lacking is, I haven’t seen an example of an FOI [freedom-of-information] request done by a local media organization that’s begotten local reporting.”

Mr. Andrews’s smoke-in-the-sky reference wasn’t just a metaphor. “One thing that has been playing out for months now is a crime story. We have a firebug that’s at play in Guelph and Wellington County. The number [of fires] is approaching about 20 over the last 18 months.” (Another blaze two weeks ago in Aberfoyle, southeast of Guelph, destroyed two homes and left two more damaged.)

The reporting, Mr. Andrews says, has been variations on, “‘Here’s the latest one, and Crime Stoppers is looking for tips.’” A daily newspaper, he says, “would grapple with it in a way that other media outlets haven’t had the bandwidth or the focus or the resources to say, ‘Hold on here, this is probably a national story.’” He adds: “This is probably a public-safety problem that isn’t being described as such.”

Those are the days he wishes he still commanded the resources of a newsroom. “You reach for the holster and there’s nothing there,” he says.

Sitting now in the Guelph Today office on Wyndham Street, Mr. O’Flanagan is turning reflective. He explains that the upheaval of the past couple of years has him questioning the goal of journalism itself.

“What is its place? What is it supposed to be doing? Who does it serve?” he asks. “In the environment that exists now, with the death of papers, the loss of staff and resources for journalism, I can’t help wondering: Where is it going and what is its purpose, and do people value it? I feel that personally, I feel that in the work that I do and the grind that I’m a part of.

“Is it valuable? Do people appreciate it? What purpose does it serve? That’s a general philosophical question, I think. And I really don’t know the answer. Does the fact that a story that I do gets shared 400 times on Facebook, does that give it value? I don’t know. Do you know?”