Vacant skyscrapers are an ‘albatross’ that Canada’s oil capital can’t shake off too soon

NationalPost.com

June 14, 2017

Claudia Cattaneo and Geoffrey Morgan

Naheed Nenshi was first elected mayor of Calgary in 2010 when the iconic Bow tower was rising to re-top the city’s skyline, new companies were opening their doors, established ones were expanding and luxury retailers were setting up shop.

Office vacancy in the city’s bustling core was so tight, “You couldn’t get space downtown for love or money,” Nenshi recalled.

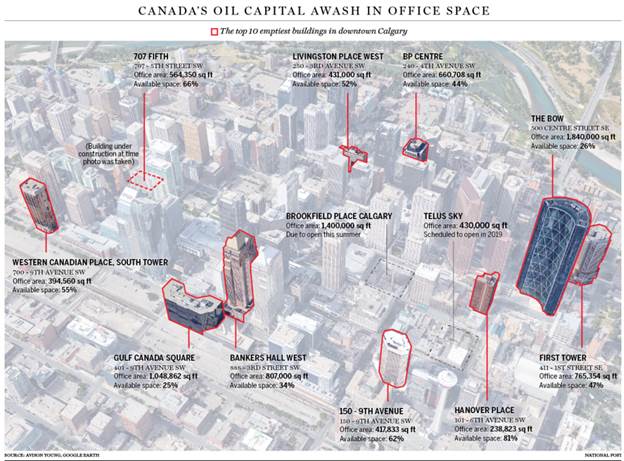

To fill the gap, skyscrapers were rapidly built — 10 million square feet between 2007 and 2016 — all underpinned by confidence in the future of Alberta’s oilsands and a business-friendly climate.

But the expansion of Calgary’s commercial core, home to Canada’s second-largest concentration of head offices after Toronto, came to an abrupt halt when oil prices collapsed in late 2014. The fallout worsened as new governments muscled in with policies to accelerate the transition to green energy.

Massive layoffs, bankruptcies, consolidation and an efficiency drive at the oil and gas survivors reduced the downtown workforce by 40,000. Put another way, one in four Calgary office workers — and their workspaces — were no longer needed.

Calgary’s office vacancy rate is so large that it’s become an albatross with implications for developers, city finances and, ultimately, taxpayers. “We went from essentially zero to almost 30 per cent (vacancy) in about 18 months,” Nenshi said. “I love roller coasters, but this is too much. The recovery will not be that quick. It’s going to be more slog work.”

Both Barclay Street Real Estate and Avison Young put the vacancy rate at 24 per cent, but it’s closer to 30 per cent for older buildings and projected to rise to 27 per cent later this year and remain high in 2018.

It’s estimated there is 13 to 14 million square feet of vacant space within Calgary’s striking cluster of glass towers. That’s equivalent to all the office space in downtown Vancouver.

Many skyscrapers, including the Bow, have completely empty floors. In others, just a handful of people occupy space where hundreds used to toil.

It will take such a long time to refill that space and Calgary may not see a new tower constructed until 2029, according to a study by the Conference Board of Canada.

Naheed Nenshi was first elected mayor of Calgary in 2010 when the iconic Bow tower was rising to re-top the city’s skyline, new companies were opening their doors, established ones were expanding and luxury retailers were setting up shop.

Office vacancy in the city’s bustling core was so tight, “You couldn’t get space downtown for love or money,” Nenshi recalled.

To fill the gap, skyscrapers were rapidly built — 10 million square feet between 2007 and 2016 — all underpinned by confidence in the future of Alberta’s oilsands and a business-friendly climate.

But the expansion of Calgary’s commercial core, home to Canada’s second-largest concentration of head offices after Toronto, came to an abrupt halt when oil prices collapsed in late 2014. The fallout worsened as new governments muscled in with policies to accelerate the transition to green energy.

Massive layoffs, bankruptcies, consolidation and an efficiency drive at the oil and gas survivors reduced the downtown workforce by 40,000. Put another way, one in four Calgary office workers — and their workspaces — were no longer needed.

Related

Commercial rents in Toronto could soar as much as 50% in the next three years as market tightens

Rachel Notley says moving part of the National Energy Board to Ottawa would be ‘dumb’

Allied Properties REIT target price boosted with Toronto office market showing “strong fundamentals”: Desjardins analysts

Calgary’s office vacancy rate is so large that it’s become an albatross with implications for developers, city finances and, ultimately, taxpayers. “We went from essentially zero to almost 30 per cent (vacancy) in about 18 months,” Nenshi said. “I love roller coasters, but this is too much. The recovery will not be that quick. It’s going to be more slog work.”

Both Barclay Street Real Estate and Avison Young put the vacancy rate at 24 per cent, but it’s closer to 30 per cent for older buildings and projected to rise to 27 per cent later this year and remain high in 2018.

It’s estimated there is 13 to 14 million square feet of vacant space within Calgary’s striking cluster of glass towers. That’s equivalent to all the office space in downtown Vancouver.

Many skyscrapers, including the Bow, have completely empty floors. In others, just a handful of people occupy space where hundreds used to toil.

It will take such a long time to refill that space and Calgary may not see a new tower constructed until 2029, according to a study by the Conference Board of Canada.

Another landlord, Centron Group, paused construction of an office tower just outside downtown on 10th St. and is considering redesigning the building to house condos. And Brookfield Asset Management Inc. put a second planned tower for Brookfield Place on hold.

No one expects the remaining energy companies, including the handful that have become giants by acquiring the assets of competitors who left the city, will need more room in the future because they want to keep their costs in check.

You will see companies that take 50,000 square feet right now (that) might take only 45,000 because they will become more efficient as technology takes over,” Kwong said. “I have been told by people in the industry, ‘We don’t need 10 engineers to drill a well any more, we only need five and a software program.’”

TransCanada Corp. and MEG Energy Corp. have put large blocks of space up for lease. Cenovus Energy Inc. has also tried to sublease space as it concentrates multiple locations into two towers. The company leased 71 per cent of Brookfield Place when times were good and is due to move in this year, but the building won’t be full when it opens.

In response, the city has launched a multi-pronged effort to attract new companies before it falls behind like a rust-belt city.

“My job is to continue to win back that business one square foot at the time and see how we do,” Mayor Nenshi said. “In Alberta, when times are good, we sometimes lose the discipline to be creative and innovative to solve our various business issues.”

Nenshi, who is up for re-election this fall, said future tenants of Calgary’s office towers will likely be smaller firms such as Nubix, a local tech startup that would have been priced out of the city’s centre in the past but which recently signed a lease for 2,000 square feet.

There are also new junior oil and gas startups subleasing space from exiting oil majors on the cheap, as well as educational institutions such as SAIT Polytechnic that are moving classes downtown.

“In the listings that I have, and the tenants that I have looking, there are a ton of guys looking for space under 5,000 square feet,” said Dan Harmsen, vice-president of Barclay Street Real Estate. “That has historically been the beginning of new growth.”

Calgary Economic Development chief executive Mary Moran is leading the charge to re-populate the downtown, which she believes will require a “conversion” from a major oil centre into a more diversified hub of clean tech, financial services and Internet-related companies attracted by the city’s unique network of indoor bridges known as the Plus15 system.

The bridges connect most of the skyscrapers downtown and were built to address the Canadian oil and gas sector’s practice of having frequent meetings.

Moran and her team have been to Silicon Valley six times this year, pitching companies in growth mode on Calgary’s more affordable office space, available workforce, proximity to the Rockies and the two-hour-long direct flights.

In addition, U.S. President Donald Trump’s policies that make travel difficult for some employees mean there is demand for “a safe haven to put people, particularly coming from India, the best engineers in the world, who can’t get in and out of the U.S. very easily,” Moran said.

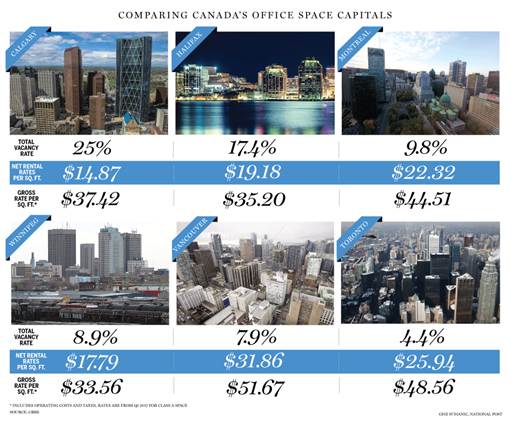

The city is also trying to attract business from other parts of Canada where office space is more expensive, housing costs are rising and labour is in shorter supply.

“I have had conversations with very large Canadian firms and said, ‘You are getting priced out of your expansion in downtown Toronto or downtown Montreal. Why don’t you consider moving some of your business units to Calgary?’” Nenshi said.

In Toronto, downtown office leasing rates are hovering around $40 per square foot; in Vancouver and Montreal, the top end rate is $30 to $33, Kwong said.

On the supply side, Calgary is looking at converting office buildings into residential spaces, but only a handful of the 96 buildings in Calgary’s core are candidates for condo conversion.

Todd Throndson, managing director at Avison Young, said the cost of addressing the mechanical, plumbing and structural issues needed to turn office towers into condos makes that idea unrealistic, as does the residential market’s high vacancy rate.

He said more needs to be done to help the city’s dominant oil and gas industry.

“We have different levels of government not helping those businesses as much as people would like them to help,” Throndson said.

Kwong said the main reason for the city’s high vacancy rate is huge unemployment. Calgary has the highest unemployment rate of any major city in Canada at 9.3 per cent. If the 40,000 downtown workers laid off by the energy sector downturn were re-hired, each taking up about 250 square feet, office buildings would be full, he said.

In the past, he added, recessions were solved by a recovery in oil prices, not diversification.

“We will probably chip away a little bit by bringing a few tech companies here, by repurposing a few buildings, but three or four years down the road, oil will be back to $80 again, and that will help,” Kwong said.

The disappearance of such a large number of employees has also hit downtown retail shops and restaurants hard, leading to the loss of city staples such as Riley & McCormick, the Western-wear store that closed in 2016 after 115 years, and Abruzzo Ristorante, a lunchtime favourite for 29 years.

When so many people leave downtown, they “also take their wallets with them,” said Maggie Scholfield, executive director of the Downtown Calgary Association, which represents more than 3,000 businesses. “Because so many of them were highly paid, they were going out for lunch, they had expense accounts.”

Empty retail space at street level makes the downtown look even emptier, she added. The upside, however, is that there are lots of sales, restaurants have cut prices and parking is plentiful.

Schofield said the transition to a more diversified business mix will take time, perhaps a decade, and require a lot of focus.

Historically, it’s been hard for other industries to flourish because the oilpatch hired all the available workers and used all the available services.

But even if the oil industry recovers, it’s unlikely to return to what it was, she said, adding that the amount of space needed is also declining because of more open-concept layouts and more workers working from home.

In the meantime, real-estate industry insiders, politicians and taxpayer groups believe the municipal government could help by reducing business and non-residential property taxes.

The municipal portion of non-residential mill rates has increased 50 per cent between 2008 and 2016, according to the city’s budget. The city in 2008 collected $390 million in non-residential property tax, but that ballooned to $820 million in 2016 as a result of both the city’s growth and tax growth.

Business owners in Calgary pay 3.86 times more municipal tax than city residents, according to the Canadian Federation of Independent Business. A recent CFIB survey showed 36 per cent of respondents would move outside Calgary to suburbs such as Okotoks to reduce overhead costs.

“Calgary city council has a long way to go to address the real problem of what is driving these property tax increases, which is municipal spending,” said Amber Ruddy, CFIB’s Alberta director.

Corporations can’t vote in municipal elections, so when money is needed from somewhere, it generally comes from non-residential property taxes, said Barclay Street’s Dan Harmsen.

“It is impacting landlords’ ability to do deals with tenants, to lease space, because today net rents have dropped by two thirds approximately, operating costs have not gone down at all,” he said.

In the past, operating costs, which include utilities and municipal tax, accounted for about a third of rent costs, now it is at least 50 per cent. In many cases, landlords are willing to give tenants space for free if they pay for operating costs and commit to a long-term lease.

Property taxes today range from $5 to $8 per square foot and “at the end of the day, I think taxes need to be reduced,” Harmsen said.

A trickier problem, Moran said, is the lack of awareness and willingness by governments — particularly Ottawa — to acknowledge how the transition to cleaner energy is impacting the city.

According to a preliminary Conference Board study, commissioned by Calgary Economic Development and going to city council on June 19, “these downtown office struggles have huge implications for the City of Calgary, since it has recently generated close to a third of its non-residential property tax revenue from this market.”

The result is that the tax burden is shifting outside the downtown where the non-residential market is more diversified, the study said in its executive summary, a copy of which was obtained by the Financial Post.

Although Alberta’s economic growth is recovering after two devastating years, Ottawa thinks “their problems are over with Alberta,” Moran said. In reality, the province is experiencing a jobless recovery.

She said it’s absurd that Ottawa is placing Canada’s new infrastructure bank in Toronto instead of Calgary where both space and expertise are plentiful, while also considering moving parts of the National Energy Board from Calgary to Ottawa because it’s too close to the energy community.

“We have to be very proud of what the energy industry has done with becoming more lean and more efficient,” Moran said. “But the trickle-down effect is that now the real estate industry is standing there holding the bag, and we have a whole bunch of (unemployed) people in the streets wondering what their next move is going to be.”