How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Yonge Subway Extension

Put yourself in York Region's shoes for a moment.

Torontoist.com

July 14, 2016

David Fleischer

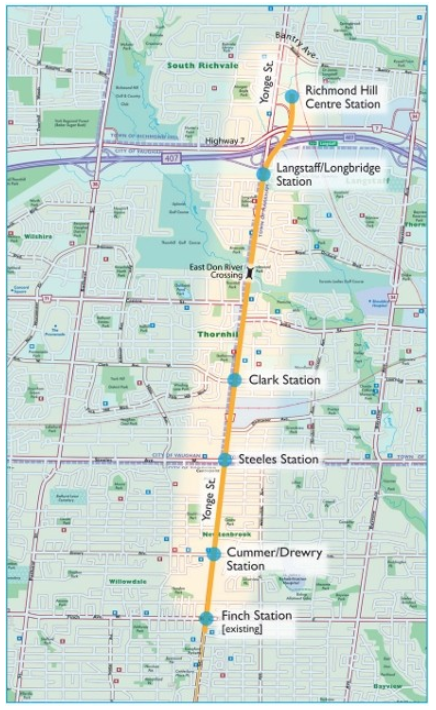

While the Scarborough subway circus is in full bloom, you may miss the hullabaloo surrounding another suburban plan, the Yonge North Extension. It would take the Yonge subway seven kilometres north from its current terminus at Finch, across Steeles Avenue and into York Region. While the subway “to Richmond Hill” does terminate just inside the town’s south border, it mostly runs through Willowdale and then Thornhill, which is divided at Yonge Street between Markham and Vaughan. After a decade of near stasis, York Region politicians are starting to ruffle some feathers. They requested infrastructure funding from the Prime Minister, and now they have launched a petition and website designed to rally support.

It’s easy to see in it a microcosm of everything we’ve been doing wrong with transit for a generation.

There are three subway projects in various stages of planning in Toronto right now with a negative correlation between how close they are to being built and how much they’re needed.

The Scarborough subway is all too familiar. Barely-planned, expensive ($3.2 billion!), compromised to accommodate Smart-ish Track, not serving many riders, controversial—but fully funded. More or less.

The Downtown Relief Line (DRL) is needed to get people away from the system’s capacity pinch point at Yonge-and-Bloor, and while planning for the line is moving forward thanks to it’s still years away and going to cost at least $3.2 billion for the first phase. (The real relief comes when it goes up to Sheppard Avenue but there’s no timeline for that.)

But only the Yonge extension is (condtionally) approved by city council, its Environmental Assessment has gathered dust since 2009. The projected costs are around $4 billion and, as with the DRL, no source is earmarked. Unlike that other suburban subway, the extension is expected to add so many new riders that it will potentially push Yonge-Bloor past the breaking point and overwhelm the system.

So, we can’t build subways that won’t generate enough riders and also we can’t build subways that will serve too many. Feel free to facepalm.

There’s a perfect storm of problems here. One of those is that not all suburbs are created equal and very few of them match the stereotypical issues we have come to identify them with.

Toronto has a series of legitimate concerns, but let’s take a deep breath and try to see things from York Region’s perspective for a minute.

The provincial planning regime emphasizes intensification and Markham, Vaughan and Richmond Hill are among the few municipalities to treat the mandated 40 per cent intensification minimum as something other than a maximum. So, York Region is doing precisely what the province requires, and with less infrastructure than promised. When it comes to the touchy capacity issue, they hang their hats on a Metrolinx report that showed there’s a sliver to exploit, if other things are done correctly.

Whereas Scarborough has precisely zero new residential units planned and whereas even Jennifer Keesmaat proclaims it “isn’t yet ready” for intensification (though the city designated it a node in 1981), plans are already in place along York Region’s subway corridor for more than 50,000 new residents and (hopefully) jobs to match. Markham and Richmond Hill brought in world class urban design firms to harness a unique convergence of transit and create precisely the sort of transit- and pedestrian-oriented centres we say we want to see in the suburbs. Toronto is also updating its Secondary Plan for the area, making this arguably the single biggest potential intensification corridor in the region.

Condo developers are taking advantage of the new zoning rather than waiting for the subway. In response to this demand, 2,500 buses rumble through the corridor every day, spewing fumes, chewing up the roads and making travel awfully inefficient for local transit users. Indeed, for all the concerns about how the extension will make it easier for 905ers to take seats away from downstream 416 riders, there are already thousands every day biking, busing and especially driving to Finch Station already.

While the 416 has its share of internecine squabbles, the family circled the wagons when uppity 905 York Region officials met with the Prime Minister and then got provincial money to advance their engineering work, the Toronto Star ran two opinion pieces slamming them for stepping out of line.

The latter piece by the usually reliable Edward Keenan is either a mean-spirited dig or ironic comic riff, depending on your point-of-view. He describes one part of Vaughan as a “dystopian suburban Hellscape,” neglecting to clarify for readers that the area is 15 km away from the subway corridor. That’s about as geographically germane as touting the Beach’s Queen East strip in relation to Scarborough Town Centre. Sure, it’s good for a laugh at Vaughan’s expense so why not trot out passé suburban stereotypes, describing the entire city as something out of Mad Max? But this doesn’t help inform readers, and perhaps after building horrible sprawl for decades we should encourage and not slam municipalities that are trying to do better.

So where does all this leave us?

Well, years of neglect, political cowardice, poor growth policies and austerity are coming back to bite us in the ass. We know what we have to do, particularly in the suburbs—and, even better, they’re down with the program—but we’ve dug ourselves a hole. Scant, unreliable funding has pitted municipalities against each other. This creates an unending and false urban-suburban dichotomy among neighbours with shared interests.

If we don’t build the Yonge extension soon, we’re making it harder for suburbs to confront challenges like greenhouse gas emissions and gridlock. If we do build it, especially without the DRL, riding the subway at rush hour is likely to evolve from the current crowded, dehumanizing swarm into something potentially dangerous.

What can actually get things moving forward? Regional politicians and municipal staff could work with one another instead of constantly being at odds. We should have a mature discussion with citizens about ongoing, stable funding for transit that makes it easy for the human beings who actually ride the system, even if they happen to live across an arbitrary geographic line. We can treat transit like a vital region-building tool and not a platform for pork-barrel spending. We could even learn from our mistakes rather than repeating them ad nauseam.

How about all that, for a change?