Shaping Toronto: Centennial Projects

The local legacies of Canada's 100th birthday in 1967.

torontoist.com

Feb. 24, 2016

By Jamie Bradburn

From neighbourhood tree plantings to the international spectacle of Expo 67, Canada proudly celebrated its centennial. The stylized maple leaf logo graced everything from historical sites to reservoirs. Cities and towns applied for governments grants to spruce up parks, restore historical sites, and build attractions to last long after the centennial spirit faded.

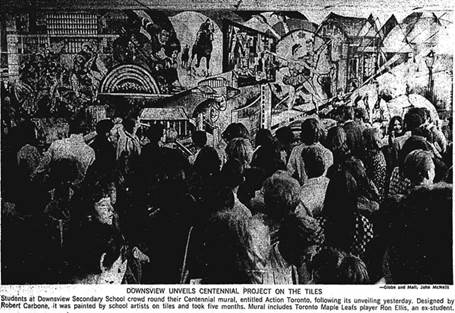

Across Toronto, many legacies remain of, as Pierre Berton’s book on 1967 termed it, “the last good year.” There are the community centres and parks in the pre-amalgamation suburbs with “centennial” in their name. Celebratory murals lining school walls. Caribana and its successors celebrating Caribbean culture each year.

Many of these projects received funding from programs overseen by a federal commission, whose work sometimes felt like an Expo footnote. “They felt like poor cousins,” British author Peter Ackroyd observed. “Expo was so big, so appealing, so clearly headed for success that it discouraged those who were plodding away on the less focused, something-for-everyone program of the Commission.”

As is our habit, Toronto wanted spectacular major centennial projects. As is also our habit, they were mired in bureaucratic squabbles involving penny-pinching city councillors, politicians and pundits who swore delays embarrassed us in front of the rest of the country, and bad luck.

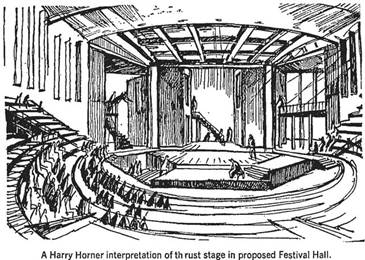

Discussions over marking the centennial began in earnest in September 1962 when the Toronto Planning Board proposed a $25 million cultural complex. With financial pruning, this evolved into a $9 million centennial program focused on the St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts, which included a repertory theatre, arts and culture facilities along Front Street, and a renovation of the decaying St. Lawrence Hall. Proponents also tossed in an expansion of the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the AGO) and refreshing Massey Hall. Mayor Phil Givens supported the project wholeheartedly - during his re-election campaign in 1964, he said “I have never been so sincerely convinced in my life that something is right.”

A key opponent was councillor/former mayor Allan Lamport, who believed the city couldn’t afford the project, and was only willing to support the St. Lawrence Hall rehab. “He is barren of ideas concerning what the city might put in its place,” a Globe and Mail editorial criticized. “It is this sort of negative approach which could find Toronto celebrating the nation’s birthday with nothing more impressive and enduring than a pageant in the Canadian National Exhibition grandstand.”

The fate of the St. Lawrence Centre see-sawed over the next few years, as council battled over the budget. When it was clear the project wouldn’t be remotely ready for 1967, the city switched its focus to St. Lawrence Hall. When the 1960s started, the site was split among several owners, and there was at least one proposal to replace it with an office building and parking deck. Under the leadership of a committee of local architects and construction officials, the restoration of the hall appeared to be on track as 1967 dawned.

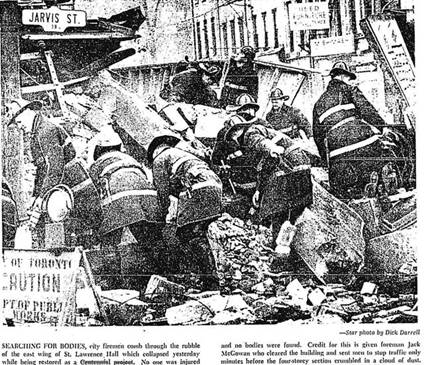

On March 10, 1967, the northeast portion of the building collapsed. The press offered unanimous support to keep the project going, such as the following Star editorial:

The restoration of the old St. Lawrence Hall was one centennial project upon which everyone in Toronto was happily united. Today, when a section of the building lies in rubble, we can be sure the determination that it will live in its former glory is stronger than ever…it wasn’t until the report of the collapse that most of us realized how much the restoration of the historic old hall was coming to mean in this centennial year, troubled with apathy and dispute over other projects...Our appetite for history has been whetted and we need the completion of the St. Lawrence Hall to satisfy it. So light the torches and beat the drums, we’ve got a building to raise.

While the restoration endured further delays from a series of city-wide construction strikes (which prompted the city to sneak in concrete via the back entrance), the refurbished St. Lawrence Hall celebrated its rebirth when Governor-General Roland Michener officially re-opened it during a December 28, 1967 gala.

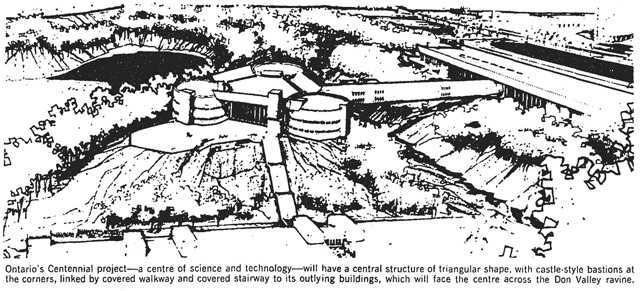

The St. Lawrence Centre finally opened in February 1970, several months after another delayed centennial project. When the province announced a science museum in 1964, it chose 180 acres of parkland at Don Mills and Eglinton. The city opposed the suburban location, preferring the CNE grounds, where Givens felt there were better connections to highways and transit. Unless the province provided compelling reasons regarding the CNE’s unsuitability, he threatened to hold up the transfer of the Don Valley site. The province wasn’t moved. Initially known as the Centennial Centre of Science and Technology, the project suffered numerous construction delays and bureaucratic bickering before opening as the Ontario Science Centre in September 1969.

Other local centennial projects had smoother rides, even if they occasionally ruffled egos. Leaside was the first to complete theirs, a community centre in Trace Manes Park which opened in September 1966, mere months before the town was absorbed into East York. The latter unveiled their major project, the restoration of Todmorden Mills, in May 1967. Mayor True Davidson scornfully called Leaside’s project “a change house for tennis players,” while touting Todmorden as “one of the most ambitious projects in Metro.”

The work on St. Lawrence Hall and Todmorden Mills demonstrated what Pierre Berton later called the true legacy of the centennial: recognizing the value of local heritage.

In 1967, the idea of preserving something of the past by restoring old buildings and preserving historic landscapes was a novel one at a time when local governments were still applauded for bulldozing entire neighbourhoods in the name of “urban renewal.” The Centennial marked the beginning of the end of that philosophy. “Heritage” had come into its own when Victorian mansions that had once seemed grotesquely ugly began to be viewed as monuments to a gilded age. Old railway stations, banks, even 1930s gas stations would be seen as living history lessons.

So far, the upcoming Canada 150 celebrations show little of the fervour associated with the centennial. An August 2014 city report recognized that the influx of legacy projects associated with the Pan/Parapan Am Games made it unlikely there would be similar scale construction to mark the country’s 150th birthday next year. A more recent report promotes marking the occasion through cultural festivals and community heritage programs. Unless an enduring celebration like Caribana/Caribbean Carnival emerges, it’s likely the reminders of 1967 will outlast those of 2017.