SmartTrack Plans Unravel

Steve Munro provides in-depth analysis on the latest transit report, which sees Toronto take on substantial risk for six SmartTrack stations.

Torontoist.com

Nov. 1, 2016

Steve Munro

Today, Toronto’s executive committee will debate a report on SmartTrack that was originally planned for a week ago. Consultations with the province were blamed for the delay, but that is only part of the problem for SmartTrack and Toronto’s transit projects in general.

City staff provide three pages of recommendations that boil down to:

- Approval of terms for an agreement with Queen’s Park on SmartTrack and the Eglinton West LRT extension, as well as a staging process to ensure that there are checks on the project design and costs at critical points.

- Settlement with Queen’s Park of outstanding charges related to the Georgetown Corridor expansion project and for GO’s capital expansion costs.

- Proceeding with planning for six new SmartTrack stations to be built at the City’s expense, as well as Official Plan support for “transit supportive policies” at SmartTrack and GO Regional Express Rail (RER) stations.

- Continuing with design work on the Eglinton West LRT from Mount Dennis to Pearson International Airport coupled with a request for funding of the segment from Renforth Gateway to the airport by Mississauga and by the Greater Toronto Airport Authority (GTAA).

- Budgetary provision for SmartTrack both for predevelopment work in 2017-18 and for the full project in 2017-26 including the City’s share of costs related to five grade separations on GO’s network.

- Review of funding and financing strategies for SmartTrack from various revenue sources.

What Is SmartTrack?

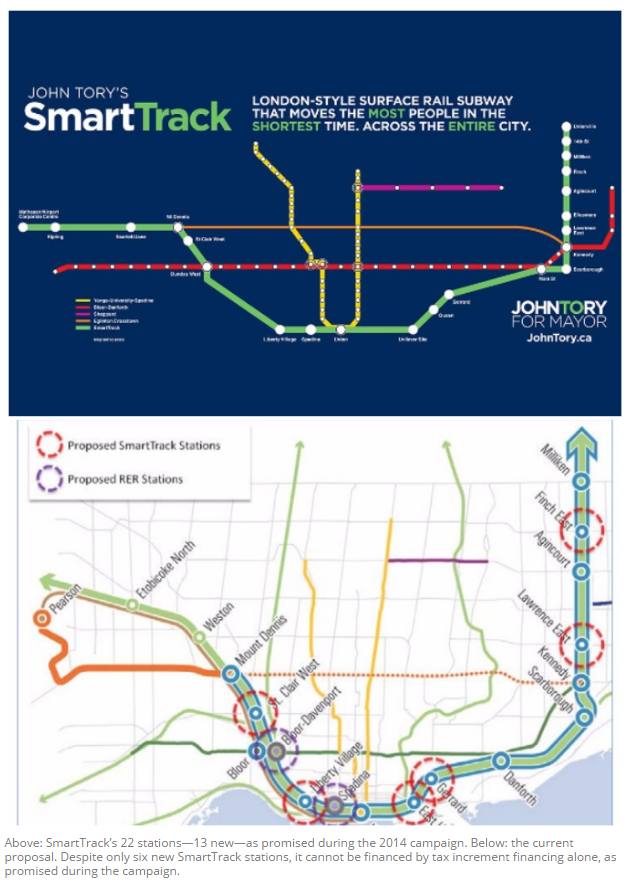

When John Tory campaigned on the SmartTrack scheme, it would involve frequent “subway-like” service linking Markham to the Airport Corporate Centre via Union Station with a total of 22 stops.

SmartTrack is now really two separate projects:

- Addition of six stations to the GO network allowing for better access to GO RER by riders within the City of Toronto.

- Extension of the Crosstown LRT line from Mount Dennis to at least the Renforth Gateway (connecting with Mississauga’s BRT network) and possibly north to Pearson airport.

These projects have nothing in common with each other beyond the fact that Eglinton West’s LRT replaces SmartTrack on the map, but with a very different design. Indeed, “SmartTrack” has retrenched so much that the cost of the GO network portion is less than half of the total proposed spending.

Service on the GO network will not be enhanced beyond GO’s current RER plans, and the only difference SmartTrack will make will be the addition of six stops at a cost of over $1.25 billion. All trains will stop at all stations. Contrary to early expectations, there will not be a separate set of SmartTrack trains serving the additional stops while GO RER trains run express primarily to serve travel to and from the 905.

On Eglinton, the Crosstown LRT service is costed all the way to Pearson airport at a total of $2.47 billion, but the City intends to pay only to the Renforth Gateway at the Mississauga boundary. Unlike the central part of Crosstown, a provincially funded project, the cost of this extension is entirely on the City’s account because it is part of the SmartTrack plan even though it is an LRT line. Roughly $700 million of the total cost lies outside of Toronto for the link north to the airport.

Of the $3.72 billion total, Toronto hopes to recover one third from the federal government, and a further $470.1 million from Mississauga and the GTAA. This leaves the city facing $2.01 billion, of which nearly 60 per cent is for the Eglinton West LRT. That number could rise as the design is refined to include up to five LRT grade separations.

Debate over SmartTrack will be complicated by treating these two projects as if they were one. The only common factor is their descent from Tory’s original campaign promise. Indeed, the Metrolinx demand that Toronto commit funding by November 30, 2016, only applies to the six new SmartTrack stations on the GO network. The Eglinton extension is much further from requiring a commitment beyond design work.

What Would Toronto Pay and What Would This Fund?

If Council approves this report, they will be on the hook for $288 million, made up of:

- Predevelopment costs of SmartTrack up to “Stage 5,” the contract award for construction of the six new stations ($71 million).

- Payment of the outstanding balance for grade separations and utility work in the Georgetown corridor ($95 million).

- 15 percent of the cost of five RER grade separations ($62 million).

- GO capital expansion costs ($60 million).

The six new proposed SmartTrack stations will be located at

- Finch East on the Stouffville corridor

- Lawrence East on the Stouffville corridor

- Gerrard on the Lakeshore East corridor

- East Harbour (the Unilever site) on the Lakeshore East corridor

- Liberty Village on the Kitchener corridor

- St. Clair on the Kitchener corridor

All of these require substantial work to fit within the rail corridors and Metrolinx has not yet confirmed the technical details.

In one case, Lawrence East, construction of the station might conflict with the existing Scarborough RT operation. It might be impossible to build this station until after the Scarborough Subway Extension (SSE) opens and the SRT is decommissioned. Other stations face geometry problems with the need for long, straight stopping areas. Metrolinx has not yet confirmed that all of the stations can actually be built.

The cost of these stations is estimated at $1.25 billion. If this work proceeds, Toronto will have to fund direct operating and maintenance costs for the stations, as well as any indirect costs such as the need to run more trains due to slower speeds on the SmartTrack corridors. Moreover, the current GO RER plan does not provide for through service at Union, and so riders on the western and eastern legs of SmartTrack would not have a transfer-free trip to the other half of the line. If Toronto wants that feature, the city would pay the extra cost of any changes, including balancing frequencies between the two legs. None of these costs have been estimated.

The five grade separations would be at Steeles and Finch on the Stouffville corridor, and at three locations in eastern Scarborough on the Lakeshore corridor. This is actually separate from SmartTrack itself, and the work is triggered by increased service levels on GO.

Other grade separations will be dealt with in future negotiations, and there will be City costs for utility relocations and any concurrent upgrades beyond the basic rail infrastructure projects. Notable by its absence from the list is the major project to provide rail-rail separation of the Stouffville and Lakeshore corridors at Scarborough Junction so that frequent services on the two corridors do not conflict.

Queen’s Park seeks to lock Toronto in to paying off outstanding debts claimed from the city (including sunk costs for the abandoned Scarborough LRT project) and for future costs of construction and operation on GO and on the LRT lines.

Since 1998, GTHA municipalities have been billed for part of the cost of GO’s expansion, although many have chosen not to pay their tithe because they regard the sharing formula as outdated and unfair. With the range of services Metrolinx will provide becoming less focused on downtown-bound commuting and more on regional travel, agreement on a formula becomes even harder to achieve. The total of the unpaid bills to date is over $1 billion.

Queen’s Park now agrees that Toronto’s SmartTrack contribution will be counted as addressing their GO obligations up to 2024-25.

The $60-million payment will be used to construct two new GO stations serving the Barrie corridor:

- A station at Bloor and Lansdowne addressing issues raised by the Davenport Diamond grade separation project. The city will be responsible for providing a connection from the new GO station to Lansdowne subway station, and this cost is not included in the report.

- A station on the north side of the rail corridor at Spadina and Front. Barrie trains would terminate at this new location releasing capacity at Union for additional service on other corridors. The report is silent on how this station might affect alignment choices for a relief subway line that could act as a downtown distributor for the new GO terminal.

Beyond the $288 million

Toronto will commit to fund the operating and regular maintenance costs for the LRT lines on Eglinton, Finch and Sheppard. Capital maintenance—replacement and major reconstruction of infrastructure and vehicles at the end of their lifetimes—would be paid for by Ontario in a few decades when that finally comes due.

Revenues (e.g. fares and advertising) on the LRT lines will flow to Toronto, and the City will set both fares and service levels. Because “SmartTrack” will really be part of GO’s operation, revenue sharing and fares are more complex. It is unclear whether “City” fares would be offered only at SmartTrack stations or at all stations on the Kitchener and Stouffville corridors within Toronto. Moreover, the report is silent on whether other corridors within Toronto (Lakeshore, Milton, Barrie, and Richmond Hill lines) will ever be part of SmartTrack’s pricing.

This arrangement effectively means that:

- Ontario will pay 100 per cent of the cost of building and equipping the already-announced LRT lines, as well as future capital maintenance costs.

- The cost of building and equipping the Eglinton LRT extensions will be shared by the city and other governments or agencies, although the lion’s share will be on Toronto’s account.

- Ontario will own the LRT lines whether they pay for them or not.

- Toronto will pay 100 per cent of the operating and maintenance costs of the LRT lines and extensions within the city itself. A contribution for the airport link from Mississauga and the airport authority would be negotiated as part of any deal to build and operate this segment.

Since Ontario announced it would pay for the LRT projects, many on council have believed that this included future operating costs. This would have seen a return to provincial operating subsidies beyond the small amount of gas tax that Toronto now uses for that purpose. This was not to be, and the City report confirms that future operating costs will all be charged to Toronto. Moreover, the City is expected to sign up for these costs now even though the full effect on future budgets is unknown.

The TTC will operate and manage the LRT services, but maintenance of vehicles and infrastructure, as well as station operations, will be handled by the province’s private sector partner as part of the already-signed contract for the Crosstown project.

The projected operating cost of the initial stage of The Crosstown LRT is estimated at $80 million (2021$) to be offset about 50 per cent by savings in bus services and new fare revenue from increased riding. Comparable figures for the other LRT lines have not yet been calculated.

This is similar to the situation Toronto finds itself in with subway proposals where net new operating costs have been ignored until long after a project is under construction. The Spadina subway extension to Vaughan is expected to add $30 million (net) to the TTC’s costs in coming years, but this number has only recently appeared in budget projections. New rapid transit lines do not operate “free” especially when they have the substantial infrastructure of a tunnel and underground stations.

For the new projects, this issue will be addressed as an integral part of the project approvals.

For SmartTrack itself, Toronto will pay for operation and maintenance of their six stations as well as any marginal costs required for service beyond GO’s RER plans.

Whatever Happened to Tax Increment Financing?

When he first proposed SmartTrack, candidate Tory claimed that its cost would be covered by “Tax Increment Financing.” The scheme would operate roughly like this:

- In the absence of SmartTrack and development it would stimulate, the City would receive a certain amount of tax revenue based on anticipated growth.

- SmartTrack would stimulate additional growth around stations, although this would be partly offset by growth further away that might not occur because of poorer transit access. On a net basis there would be new tax revenue directly attributable to SmartTrack’s presence.

- The extra revenue would be used to finance the transit infrastructure.

That’s the theory, but it runs headlong into several problems. The City now has a tax rebate program to encourage certain types of development. This involves forgiving any new taxes for 10 years after construction. In effect, there is no “tax increment” to collect on such properties. City staff acknowledge that this incentive might have to be discontinued so that TIF actually generates its promised revenue stream. In other words, the city would drop its tax incentive, assume that development would still occur because the new transit lines are so attractive, and the new tax revenue would help pay for the transit projects.

A further problem is that new buildings require new services, and if their incremental tax goes to paying for SmartTrack, that revenue is not available for general services including transit subsidies.

The study reviewing the application of TIF to SmartTrack considered the line in its full, original scope with many more stations, and more areas where related growth would occur. Now that SmartTrack is only a handful of new GO stations where considerably less service will operate than planned, plus an LRT through residential Etobicoke, both the number and attractiveness of the sites have diminished. The LRT will bring benefits to the airport district, but the TIF benefits would flow to Mississauga, not Toronto.

The “TIF zones” within which tax increments would be collected are sited around many stations that are not part of SmartTrack, but would receive some improved service through the RER plans such as Agincourt station in Scarborough. The increment in such zones, if any, is not due to SmartTrack and yet it may have been counted as potential revenue.

At the time of writing this article, the City has not confirmed whether they used all of the zones in their estimation of TIF benefits, or only those inside Toronto with SmartTrack stations and the Eglinton corridor.

[See map 2 in this PDF for TIF zones.]

How Will We Pay For SmartTrack?

City staff report these projects will have to be financed through debt and funded through three revenue streams:

- Development charges (DCs)

- Tax Increment Financing (as above)

- Property tax increases or equivalent other revenue sources.

A basic problem with both DCs and TIF is that until development actually occurs, there is nothing much by way of upfront DCs or ongoing marginal taxes to collect. Therefore in the short term, the City’s other revenue streams, notably the property tax, is on the hook to fund this debt. If development is slow to materialize, this situation continues into the period when “free money” was supposed to pay for the project.

The timing and amount of any tax increase will be affected by various factors including when work actually occurs and is billed to the city by the province, the proportion of TIF revenues and DCs that actually materialize, and whether the city opts to defer repayment of capital debt until the revenue streams build up to support it.

With the standard approach to financing, a property tax increase of 2.1 to 3.9 percent would be needed based on the level of TIF revenues. This could be reduced to a range of 1.0 to 2.0 percent with a scheme called “revenue matched financing.” This is not unlike a back-end loaded mortgage where the future payments rise after an initial “holiday” during which one’s income, in theory, would rise to meet those higher costs.

All of this leaves the City gambling on whether future development will occur when and where it is wanted, that it will provide the expected revenues, and that taxpayers won’t wake up someday facing a bill because their lottery tickets didn’t pay off. Indeed, City staff recommend that at most 50 per cent of projected TIF revenues be included in the project budget in case developments don’t work out as planned.

Most of the costs cited here are in year of expenditure, that is to say inflation has been built in. However, there is a substantial added cost related to procurement through Infrastructure Ontario for financing and for risk transfer to private project partners. The public sector must pay a premium in order for the private sector to accept risks in taking on construction and ownership, and the hope is that this fixed premium is less than what might have been spent on overruns. That premium will add to all of the cost estimates, but a specific figure has not been included in the staff report.

Scarborough Update

A separate report on the Scarborough Subway Extension is due out in December 2016. This should include a final recommendation on the subway’s alignment and projected cost, as well as an update on the Eglinton East LRT proposal.

In the proposed agreement with Ontario for the SmartTrack package, two numbers for the Scarborough projects are confirmed:

- Ontario will contribute $1.48 billion (2010$)

- The sunk costs of the Scarborough LRT project plus anticipated penalties for its cancellation of $78.4 million will be deducted from this amount.

Can Toronto Make A Decision?

There is no question that Toronto has under-invested in transit and other infrastructure for years, and that the holy grail of tax reduction trumps any move to actually pay for the many projects so badly needed. A tax increase of some form is inevitable, but the real questions are how much and how soon.

How much depends on which projects the City actually decides to undertake. Photo ops are cheap, but actual construction does not happen without real money on the table.

When depends a lot on the target date for completing these projects. We now know that SmartTrack and Eglinton’s LRT extension stretch out to 2026. Some services, notably GO RER, may be in service sooner, but it will be a long wait for what remains of John Tory’s signature plan to actually carry riders.

Meanwhile other transit projects like the Scarborough subway, the relief line, and waterfront LRT vie for attention both at council and at other levels of government. Dates for these drift far enough into the future that any assumptions about shared funding based on current government policies would be long-obsolete.

Toronto seeks three key principles in its negotiations with Queen’s Park:

- Planning will be on a network basis, not on individual projects.

- Cost, revenues and risks will be equitably distributed between both governments.

- Toronto contributions will add to total spending, not replace provincial commitments to GO RER and the LRT projects.

The only time-sensitive issue is the six SmartTrack stations and their incorporation into RER construction contracts. However, Toronto now faces a demand from Queen’s Park to accept a package deal without knowing the full implications of commitments it faces for the complete network. Whether the province will strong-arm the city into accepting all of its terms as the price for the remnants of “SmartTrack” remains to be seen.

Toronto faces a hard decision to actually commit to, not just posture and talk about, major improvements in its transit network. This is only the first of several decisions that could transform the transit network over coming years, but it comes at a time when the watchwords are “cut, cut and cut again.” Beautiful new rapid transit lines will be useless if, by the time they actually operate, the transit system around them has dwindled into irrelevance thanks to starvation funding.

Links to Reports

Transit Network Plan Update and Financial Strategy

Presentation to Executive Committee

Summary Term Sheet and Appendix A – Stage Gate Process

City Funding and Financing Strategy

Regional Express Rail Grade Separations Planning and Technical Update

New SmartTrack and RER Stations Planning and Technical Update

Eglinton West LRT Planning and Technical Update